Home is normally London for Cathal Coughlan, having initially left Cork in the summer of 1983 alongside Sean O’Hagan to relaunch Microdisney, keen to pick up on interest from legendary BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel and escape a supposed ‘unpopular support band’ tag.

But right now, he’s holed up with his partner in North Staffordshire, isolating of sorts from the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’re just taking a break in the Midlands … except that we’re stuck here for the lockdown. We began by taking a break … a break that became mandatory. It’s ok though – it’s possible to get out and have a walk, which became really hard in London.”

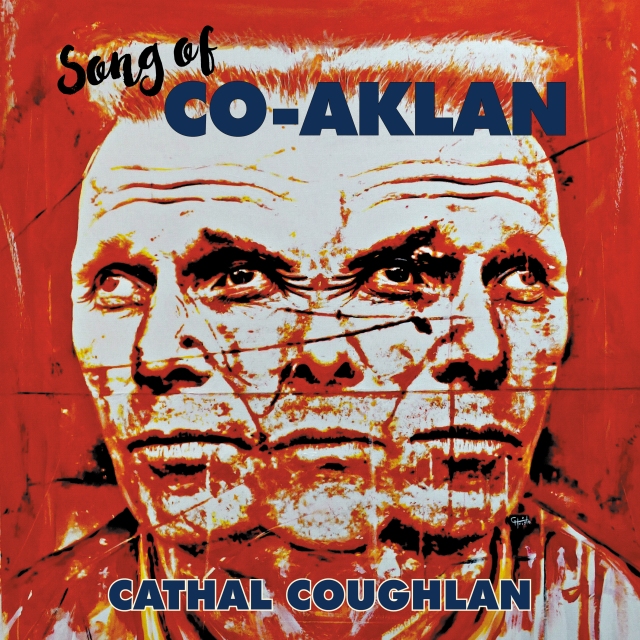

My excuse for tracking down Cathal is the forthcoming release of his sixth solo album, his first in more than a decade, Song Of Co-Aklan a compelling 12-song opus recorded in London, with guest appearances from good friends and old bandmates, including the afore-mentioned Sean O’ Hagan, Jon Fell and John Bennett (Microdisney/High Llamas), Luke Haines (Auteurs/Black Box Recorder), Rhodri Marsden (Scritti Politti), Aindrías Ó Gruama (Fatima Mansions), Cory Gray (The Delines), and Dublin singer-songwriter Eileen Gogan.

I was only a couple of listens in when we spoke, but continue to pick up more and more with every play, the first shot across the bows the sublimely-catchy lead single and title track, an accompanying video by Emmy Award-winning filmmaker George Seminara also starring Luke Haines and James Woodrow, Nick Allum and Audrey Riley (aka the Grand Necropolitan Quartet, Cathal’s long-time collaborators, drummer/percussionist Nick Allum having featured throughout the Fatima Mansions years and on all Cathal’s solo LPs).

And yet I put it to Cathal that I love how the second single is the darker, more brooding and discordant Steely Dan meets Scott Walker-like ‘Owl in the Parlour’, going from arguably the most commercial on the record to one of the least obviously radio-friendly.

“Oh, yeah!”

It’s certainly a record worth putting the extra ear-work in for, tracks like ‘St Wellbeing Axe’, with its hints of latter-day Bowie, and the slow-building ‘The Lobster’s Dream’ coming alive, the same applying to ‘Owl in the Parlour’, now among my favourites. Besides, I guess he’s got form for all that, going right back, an amazing song like Microdisney’s ‘Loftholdingswood’ initially relegated to B-side status. But while the new LP grows ever stronger for me, I’m guessing top-40 hits aren’t on the agenda.

“I wish I could say it was entirely premeditated, but it’s such a diverse-sounding record that it took a long time to come up with a running order. I’ve ended up with this thing that starts off lively, gets really intense for quite a long time, and finishes in quite a pastoral way. I hope people go for it – ha! – because I couldn’t find another way to do it.”

I agree about the way the LP is sequenced, that second half of the album my preferred half, I’d say, with so much in there waiting to grab you after repeated listenings, not least on ‘The Copper Beech’, ‘Falling Out North St.’ and ‘Unrealtime’. Getting back to the opening title track though, particularly with the chorus, I hear echoes of the Icicle Works. I guess his and Ian McNabb’s voices share certain qualities.

I agree about the way the LP is sequenced, that second half of the album my preferred half, I’d say, with so much in there waiting to grab you after repeated listenings, not least on ‘The Copper Beech’, ‘Falling Out North St.’ and ‘Unrealtime’. Getting back to the opening title track though, particularly with the chorus, I hear echoes of the Icicle Works. I guess his and Ian McNabb’s voices share certain qualities.

“It’s a fairly singalong chorus, and it’s got some very nice jangly guitar from Mr Woodrow. It does get a bit ragged in the middle part, but the idea was to be kind of contrary. There are more straightforward things on the album, like ‘The Knockout Artist’, quite near the end. I don’t really mess with people much on that one.”

There’s a song that grows on me the more I hear it, my favourite on the record, one on which Sean O’Hagan adds synth touches. It’s also one deserving wider airplay, with lots of lovely guitar, swirling keyboard, and an underlying ‘70s feel. But is there an overriding message? Does this record tell us more about where we are right now in the 2020s? And what’s ‘The Song of Co-Aklan’ about?

“It’s kind of a refracted vision of how people are being forced to live in seemingly intolerable situations, like having their homes bombed out from under them, and in the overall scheme of things it’s not seen as mattering, because so much of the wealthy part of the world has become completely numb to things that would have caused a lot of concern, even in the ‘70s.

“The ‘70s was a very turbulent time and in the ‘80s we had the Lebanese civil war and a bunch of other really long conflicts – Northern Ireland kept on going and going – and yet something like Syria seems to cause no direct alarm to anybody. And I say direct because the refugee problem and the mass migration it fuelled has contributed to other political movements as more wealthy countries try to keep those people out, even though their situation has been rendered so intolerable.

“But I’m not trying to offer any kind of solution, I’m just kind of offering a suitably broken-up vision of it. Because it is a broken reality. That’s what I’m trying to get across really – it’s a broken reality where certainties that we console ourselves with don’t work. Once a thing like that descends on you, all bets are off, and the pandemic has given us a taste, but no more than that.”

Speaking of which, I initially took a positive slant on the public reaction to the covid crisis, the public seemingly recognising the true value of health workers, carers, front-line workers, and so on. After all that divisive shite about Brexit and the General Election won on it, maybe we were waking up to what was really important – the NHS, the Welfare State, community values …

But it didn’t take long for that vision to sour, a Government seemingly more interested in awarding key contracts to cronies, freezing public sector pay while clapping along with the rest of us. And already we see the reality of false borders between the UK and Europe, media outlets stoking up ‘us and them’ attitudes, so many taken in by it all.

“Yeah, that is diabolical, the exceptionalism and very selective view of history is really fundamentally disturbing for the future of this country. When I moved here, I had a slightly Pollyanna view which is that the UK had the welfare state and had taken some measures to reform its society after the shock of the Second World War. But gradually we’ve seen so much of that reversed, done in a dishonest and ambiguous way – with sneaky privatisations and little bits of kleptocracy.

“The thing about the NHS in the pandemic is that because of this dearth of candour we have, it was possible for the whole ‘leave’ wing of the Tory party to co-opt the Thursday night applause as if they’d thought of it. And clearly there’s still no consideration given toward rewarding properly the people who have worked in the NHS through all of this or taking into account the fact that such a high proportion at certain levels were born in another country.

“It would be nice to think once the smoke has cleared, there will be some sort of evaluation. No one’s looking for a lynch-mob, but it doesn’t seem too likely at the moment that this evaluation will happen. It will just move on to the next thing.”

First time I saw Cathal was with Microdisney in December 1985 – 35 years ago last month – supporting That Petrol Emotion at the Boston Arms, Tufnell Park, North London, his imposing stage presence just part of a rich sonic and visual tapestry, this punter soon splashing out on The Clock That Comes Down the Stairs, that Rough Trade release remaining among my favourite ever LPs.

Seemingly mournful in tone, here was sheer poetry, in music and lyric form. While many of the LPs I listened to then were slowly left behind, it stood the test of time. And the following year came another corking album, the Lenny Kaye-produced Crooked Mile, this time on major label Virgin. Ahead of this interview I went back to that for the first in a very long time, having forgotten how well I knew every chord change, every nuance, so many of the lyrics coming back mid-song.

Those albums were an integral part of the soundtrack of my life around then. But only one more followed, the overall too safe and smooth (although partially good as ever) 39 Minutes proving to be their last, Sean going on to form The High Llamas while Cathal gave us the similarly-acclaimed if not wildly different Fatima Mansions.

Although it took a while, Cathal’s now rightly considered to be among Ireland’s most revered singer/ songwriters, ‘beloved by fans of caustic literate lyricism and erudite songcraft’, as current label Dimple Discs put it.

Since the demise of Fatima Mansions in the mid-‘90s, he’s released five acclaimed solo albums and taken part in an array of different collaborations, making numerous guest appearances. And there was 2019’s Ireland’s National Concert Hall Trailblazer Award – celebrating culturally-important LPs by iconic Irish musicians, songwriters and composers – for The Clock Comes Down the Stairs.

Despite that old adage about never judging a book, or in this case an LP by its cover, if an image ever sold a record, there it was for me, sold from the start by Felicia Cohen’s sleeve photograph of a busy rail intersection at Clapham Junction, soon feeling the same way about the record itself.

“I think it’s aged pretty well. There are things on it which are of their time, sound-wise, but I think they actually hold up. It doesn’t automatically follow that just because you can pretty accurately work out when something was made that it’s automatically anachronistic. There’s some great things from the ‘80s that could only have been made then – the classic for me being Prefab Sprout’s Steve McQueen, which completely works.”

Agreed. But while The Clock briefly topped the indie charts in late ’85, as former Buzzcocks manager and New Hormones label boss Richard Boon put it on Paul McDermott’s splendid 2018 radio documentary about Microdisney for RTE, ‘They should have been more than just cult heroes’.

Agreed. But while The Clock briefly topped the indie charts in late ’85, as former Buzzcocks manager and New Hormones label boss Richard Boon put it on Paul McDermott’s splendid 2018 radio documentary about Microdisney for RTE, ‘They should have been more than just cult heroes’.

I wasn’t trying to work out what resonated then, but listening back now – knowing where Sean went with the High Llamas and his love of Brian Wilson’s work, and hearing Cathal’s love of Scott Walker, Bertolt Brecht, and so on – I see how a chalk and cheese combination of Cathal’s often mournful tones – although never less than poetic, descriptive and insightful – and Sean’s bright guitar work and melodies appealed. What John Peel called, with a nod to Thomas Carlyle, ‘an iron fist in velvet glove’. And there were parallels with Prefab Sprout and Microdisney’s Aussie pals The Go-Betweens.

There’s a quote from Robert Forster on the RTE documentary suggesting ‘we were immigrants and I think that was something that pulled us together’. Both bands struggled to be heard, with very little money to get by on, sharing the same rehearsal rooms and alcohol-fuelled downtimes. I also assume there was a feeling for both bands that they had to make it big or face going home, their dreams burst. But raise their games they did, the songcraft of each act making me sit up and notice then and now. And it’s clearer now that they had in common positions on the outside lane of pop – outsiders in more ways than one.

“Yeah, we were. I think we confused people. Some of it cultural stuff. We didn’t have the agenda capabilities of the normal London music group, where it’s important to show your influences and maybe not mix your messages too much. I’m not saying we were right and they were all wrong, because frankly there were a lot more of them than us! But coming from Ireland as it was in those days, you didn’t have that kind of nous, really. It was just about finding something that worked. If it confused people, that was the price you had to pay.”

In music, football or whatever, I’ll often come down on the side of the underdog. I guess in Cathal’s case too, the accent and Irish heritage marked him out as different. A love of The Undertones and their successors, That Petrol Emotion, made me more open to that, but I guess that made it all the harder for London Irish outfits running the gauntlet on a daily basis at a time when the Troubles were such an issue, both sides of the water.

“It wasn’t overtly terrible, but there were everyday things that were problematic, like looking for a place to live when you needed to do that, and politics generally. But inside music, at least with the people who’d speak to you, there was no problem at all. It was quite a welcoming set-up in many ways. We met people like The Mekons and The Go-Betweens, and a little later, the Kitchenware people. But officialdom was a lot stickier in those days.”

Picking up on the indie factor, you were with Rough Trade, and a small number of acts on leading independent labels like Factory and Postcard went on to have commercial success. Was there a defined manifesto to do the same when you got to London, and did you know where you were headed?

“We thought we were headed for the label that became Blanco y Negro, best known to posterity as the home of The Jesus and Mary Chain, although that was still a couple of years in the future. But it was going to be this amazing kind of artistic salon, co-funded by Geoff Travis (Rough Trade) but also Mike Alway from Cherry Red and a bunch of other people.

“It didn’t really turn out like that, so there was a lot of waiting around. They did sign their name on the invoice for us to go and record most of the first album but over-committed all over town and inevitably a reckoning came. Geoff had told us if all else failed the album could come out on Rough Trade, and Sean had the presence of mind to remind him of that, so that ended up happening. But it was a weird time at Rough Trade, The Smiths just beginning to absolutely sky-rocket!”

I understand you were helping out in the warehouse with that push.

I understand you were helping out in the warehouse with that push.

“We had to re-sleeve a whole lot of ‘What Difference Does It Make?’ singles because of changes to the cover.”

While no doubt always short of cash, in a critical sense you had important backers. You mentioned Geoff Travis and Mike Alway, and there was Peel …

“Oh yeah, more than anyone else really.”

Was it six Peel sessions with Microdisney and two with Fatima Mansions altogether?

“Sounds about right. There was an awful lot of support, and the amazing thing – hard to describe to anybody nowadays – is that you could communicate with a pretty broad audience all over the UK and even Ireland and wherever people picked up UK armed forces radio, whether or not you had a record out. When you had as much coverage, session-wise, as we had, it was pretty decisive.”

True enough. We picked up on bands time and again through Peel playing them first. I guess that was the case all over, helping you play towns and cities where you had no previous links.

“It was. I’m not saying we were getting fantastic fees, but as long as you didn’t have to stay over and pay for a B&B … that was about the limit. We could just about do Newcastle, because we knew people there and could stay. We only made it to Glasgow once during that period. There was the usual pretty unsavoury driving after shows, the driver having trouble staying awake, completely sober but having difficulty. There was a lot of that.”

It was hard enough for us getting home from London, let alone heading in all directions back to the capital. Many a time I drifted off down the A3 after a few ales as a passenger after nights out in Kentish Town, Kilburn, Camden, or wherever.

Going back to that first time I saw you, I’m not even sure we caught the start of the Boston Arms set, but recall you in rant mode during ‘464’ or ‘Harmony Time’ (or both). I was aware that the early years’ collection was called We Hate You South African Bastards! and perhaps put those factors together, misremembering a major shouty moment about the evils of apartheid. Either way, it made a huge impression.

“Yeah, memory over long distance is a little bit tough. It certainly is for me. I’m not even positive that we did the Boston Arms with the Petrols.”

Well, I recently discovered an online upload of someone’s bootleg that night.

Well, I recently discovered an online upload of someone’s bootleg that night.

“Oh, really. We did the Town and Country Club with The Go-Betweens around then …”

I think that was late April ’86.

“Oh, okay.”

I should point out I only knew that because I looked it up earlier. I’m not that much of an anorak … honest. I don’t think I saw Microdisney’s Whistle Test performance earlier that year first time around though. I’d have definitely remembered that.

“Ha!”

Anyway, when did you last get back to Cork?

“Oh … that’s a sore one. September 2019. It really bites this time. If I had any idea this was coming, I would have made other plans for the latter part of that year. But there was stuff that had to be done, then this happened, and it’s the longest I’ve been away for 40 years.”

How different is Cork today from that you left in 1983 when you came over with Sean?

“In some aspects, it’s unrecognisable. I have to be really careful not to make assumptions about anything, because I haven’t spent any big chunk of time there, but in the case of Cork in particular the appreciation my generation had for music, visual art and literature from outside really blossomed for the generations since, and there is actual infrastructure that allows people to do stuff there, have their base there and have a community there.

“That wasn’t there in my time, so it’s a great thing. On the other side, they suffered through the 2008/2010 economic collapse. That really took its toll, so the progress hasn’t always been in one direction, but it could be argued that it’s still the same place, just more sure of itself, certainly on the creative side.”

Regarding your initial era here, you made lots of good friends then that remain so today. And this LP is with Dimple Discs, a label effectively revolving around Damian O’Neill (The Undertones, That Petrol Emotion, The Everlasting Yeah) and namesake Brian O’Neill, from your Rough Trade days. I guess you’ve known both for a long time.

Regarding your initial era here, you made lots of good friends then that remain so today. And this LP is with Dimple Discs, a label effectively revolving around Damian O’Neill (The Undertones, That Petrol Emotion, The Everlasting Yeah) and namesake Brian O’Neill, from your Rough Trade days. I guess you’ve known both for a long time.

“I first met Damian in 1981, I think, with the five-piece early Micro Disney (as they were then). We supported The Undertones in Salthill, a resort just on the edge of Galway. I think we drove back to Cork that night, but spent a very happy hour or so chatting to Damian, John (O’Neill), Mickey (Bradley), Feargal (Sharkey) …

“I met Brian at Rough Trade, I think that would have been 1983, probably that stint in the warehouse. Somebody last year posted a video where I think you see the side of my head. It’s not like I spent a huge amount of time there. It just happened to be the day someone was walking around with a camera. Someone else who features heavily is Nick Clift, who’s working the digital side of this album from his current home in Jersey City.”

I interviewed Nick last year about his band, the Folk Devils, their story intertwining historically with the early days of Killing Joke and links with Rude Boy leading actor Ray Gange, bringing in The Clash story and squat scene of the early ‘80s. While clearly a big city, it seems there was a relatively small community of artists around London out to make an impact, including Sean and yourself, rehearsing in Camberwell, living initially in Kensal Rise, but also with an East London link.

“East London was where are all the cheap premises were, particularly studios like that in Hoxton Square – unthinkable now. We did a lot of mixing for The Clock Comes Down the Stairs there. Yeah, even London was capable of hosting lots of rough and ready little businesses, which no way it is now.”

When you first came over, I was still 15, yet to do my O-levels, but equate Summer ’83 with the last Undertones gigs (until their 1999 return), seeing them bow out at the Lyceum and Selhurst Park.

“I remember me and Sean running into Damian and Mickey (Bradley) on Ladbroke Grove that following winter, and they were starting a group.”

Was that Eleven?

“That’s right!”

I saw them a couple of times at the Marquee. I thought they were great, felt that might be their next direction. But it wasn’t to be.

I saw them a couple of times at the Marquee. I thought they were great, felt that might be their next direction. But it wasn’t to be.

“I never got to hear them. We were pretty skint and could only go to gigs if we could get in for free.”

Well, they managed one Peel session.

“Ah, I didn’t know!”

Would you ever have thought, almost four decades later, you’d still be involved in all this? Or was that never in doubt? Did you always have that belief you were going somewhere?

“I can’t say I had the belief, but certainly had quite a lot of determination, although I’ve been prone to extremes of doubt and a lot of short-term thinking. It is quite surprising to look back now, for that reason. Even though it’s been intermittent for the last while, there’s still been live work, other people’s projects or bits of writing, and I’ve been able to keep it going.”

Are you making a living out of this? So many of us end up dabbling in other areas to ensure bills are paid.

“I’ve had to do that. It’s just a logical consequence of not selling any records! There is no mystery benefactor. You have to sustain yourself by some means. But at the moment I’ve got a bit of breathing space to try and do as much as I can.”

This new LP suggests you’ve put a difficult year to great use, as have several artists I’ve spoken to lately. In a sense it’s how we function perhaps – maybe others are getting a taste of that approach to life, having to adapt similar coping mechanisms. That doesn’t mean we’re not suffering the same mental health issues, but …

“I suppose so, although there are still times when I have to pinch myself. I nearly grab my coat to go down the shops to get a screw or a packet of nails or something, and you can only do that under quite specific circumstances. Just having that ability and breathing space to a possibly quite mundane experience that takes you outside of yourself. Even when I’ve been at home doing music seven days a week, I’d always want to take a walk around, get some vegetables or something, just to break that up, and now that’s difficult.

“I was lucky that the album was more or less already mixed and I’d been in the studio, but had quite a lot left to do. The only way I was going to get done in any reasonable timeframe was to do it myself. That pulled me through the first couple of months without any major shift. It was a case of get the head down, get the thing actually finished.

“After that, I started working with Jacknife Lee on this duo album we’ve done as Telefis. That will come out later this year. And although it’s been done remotely, it’s pretty intense in its own way – it’s not an introspective strum-along!”

Although part of you as an artist is used to working alone, I bet you miss the performing.

“Oh yeah, that would be the next logical thing to do. We just don’t know when it’s going to be possible.”

It’s all very well telling you it’s a great album, but I’m guessing you need that feel from people seeing you play in a crowded pub or whatever.

“You do. That’s when the material starts to talk back to you, and you get more of a focus on what you want to do next. That’s the thing. I’m trying hard to get stuck into the next thing and I’ve got some things I think are quite good. But it would really help to give this album a bit of a kicking in front of an audience to find out some things.”

When that finally happens – and we won’t try and put a date on it – would that involve a set based on this LP but with a sprinkling of past solo work, Fatima Mansions and Microdisney songs?

“Definitely a mix. The only slight unknown is what kind of line-up I’d have on stage. That’s partly a factor of how far you’ve got to go and how many people you can afford to bring along! To an extent that dictates what material to pick from, but I’m pretty lucky at this point there’s a lot to choose from.”

You’ve worked with a lot of those involved on this album for a while, haven’t you, like Luke Haines?

“Yeah, we’ve done quite a bit. We did The North Sea Scrolls with Andrew Müller (2012). That was the most intensive co-working we’ve had, but we see each other pretty often. When he offered to do some stuff, I was delighted, especially when it transpired it wasn’t going to be a double-bass record – it was going to be bass guitar, which wasn’t any logical decision, but he was able to fit in great. He’s totally self-sufficient in home recording.”

James Woodrow and Nick Allum also go back a long time with you.

James Woodrow and Nick Allum also go back a long time with you.

“Yeah, and Audrey, but Nick goes back the longest of all – 1988 or thereabouts.”

Last year, I interviewed Eileen Gogan – who features on understated, slowly-building finale ‘Unrealtime’, along with Sean O’Hagan – and she revealed how important Microdisney were to her growing up and how great it was to guest with you for the band’s reunion shows, and for yourself and Sean to work on her record.

“It’s been great getting to know Eileen and work with her. I was a fan of her first solo record. That’s where that started. Obviously, she’s a bit younger, we weren’t part of the same generation, although we know some of the same people. There was a real feeling of strength in having her on stage with us – a great thing for us.”

Did you keep in touch with June Miles-Kingston (who contributed backing vocals on The Clock, Crooked Mile and 39 Minutes)?

“A few social media ‘hello’s, but I haven’t seen her in a great many years.”

Her CV is certainly impressive.

“Absolutely, and the reason for getting her on The Clock was that I was so taken with the way she sang ‘Our Lips Are Sealed’ with Fun Boy Three. Her and Terry Hall were a great blend.”

You’ve not always gone for the expected. For example, when you played the Barbican with Microdisney, you finished with Frankie Valli’s ‘The Night’. I also see you covered ‘Easy’ by The Commodores back in the day. It seems you liked to surprise people.

You’ve not always gone for the expected. For example, when you played the Barbican with Microdisney, you finished with Frankie Valli’s ‘The Night’. I also see you covered ‘Easy’ by The Commodores back in the day. It seems you liked to surprise people.

“Yeah, we specialised in awkward cover versions, and that was one!”

Is that an Irish showband mentality coming through?

“Erm … we were willing to allude to it. We didn’t think it was going to win us fans, necessarily. We did ‘Woodstock’ at a couple of shows, and I think one by The Jesus and Mary Chain, who were opening for us. We also did ‘Jesus Christ’, the Big Star (Christmas) song, in the middle of a summer! So yeah, lots of really stupid cover versions.”

I guess we’d have expected you to do Captain Beefheart or something along those lines. But I like the fact you did that instead.

“Yeah – Beefheart, the Velvets … that would have been the right thing to do, but we were not going to do the right thing!”

Going back to your roots, you played a bit of piano early on. Were you the first in your family to try and make it in music? And was there always music around the house?

“Not so much around our house, but there were people in my extended family who were very talented. On my mother’s side my aunt and uncle were really great singers. My uncle’s still singing at the age of 81 – a very powerful tenor, I guess you’d say, with my aunt a soprano. Neither of them did it professionally, but they were known throughout the region for their talent.”

Looking forward to live shows when it’s safe to get out again, will those be under the Co-Aklan banner?

“I’ve an intention to evolve into Co-Aklan. That’s the plan. We’ll see what fate does to that for me.”

Is this alias you trying to spell out all these years later how to say your name properly?

Is this alias you trying to spell out all these years later how to say your name properly?

“Not really. I think I’ve had second thoughts about just going by my own name. It came to seem like a bit of an unnecessarily rigid thing to do, probably the product of the state of mind I was in back in 1989. That’s a long time ago now, so it seems I should try and do something else.”

To quote ‘Town to Town’, ‘She’s nervous and her best friend is waiting, she’s trying to pronounce my name.’ All these years on, it seems that might still be the case.

“Well, I totally get that. Both parts of my name are pronounced in different ways depending where you are in Ireland, much less California, where they have a very tough time with it.”

And outside the solo work, will there be any more Microdisney shows? Crooked Mile will be 35 next year. Or was that it with The Clock and those live shows I sadly missed?

“I think it probably was, but we had a great time doing it. I absolutely wouldn’t rule anything out, but there are no plans.”

And Fatima Mansions?

“Oh, the Mansions – haha! I mean, the fact it’s never happened apart from one semi-reunion for a birthday party means there’s nothing to tap into in terms of logistics and everybody living in widely different places. I’m not sure it could be pulled together.

“It would be fun, but could involve weight-training for six months. It would be everything Microdisney wasn’t. With Microdisney there was work to be done, but it wasn’t mad!”

Song of Co-Aklan is due to land on March 26th, with detail on how to pre-order and all the latest from Cathal Coghlan via Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or his own website.

Thanks for a great interview.

Great to see Cathal still making music and being a creative sort of a bloke.

I saw Microdisney at the Boston Arms in Tufnell Park around that time but my memory is that the Proclaimers were on the bill….

I do have to declare that Sean O’Hagan is a first cousin and so I was probably on the guest list!

I was writing for Hot Press at the time (though they were a bit shy about actually paying me) so we probably attended a few of the same gigs.

Good times, Good times.

All the best , Enda

Ha! Sorry Enda. I saw this comment a while ago and clearly forgot to respond. I was probably looking online to see if I could find anything about a Proclaimers/Microdisney bill somewhere … then got side-tracked elsewhere. It happens rather regularly, come to think of it. You’re right of course about being at the same shows at some stage. So many times I speak to people now who were in the same place at the same time, but we probably not so much as said a word to each other. As a tall fella though, most people have at some stage used me for navigation on the way back from the bar to find their mates. Re The Proclaimers bill, someone will know, of course. Anyway, I appreciate your words. All the best.

Great interview, so sad how things turned out. Good questions too.

Thanks Alan. Yes, so sad, and a real shock. Thankfully, we’ll always have this music.