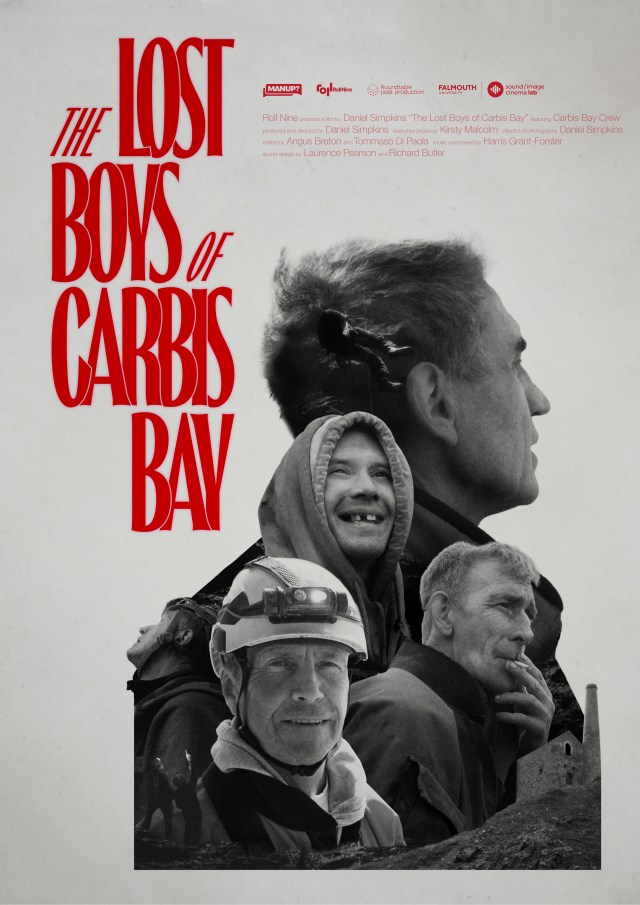

Earlier this year, the better half and I had a date at the flicks with a difference, wandering down the hill to the Regal Theatre in Redruth for the opening night of a Cornish tour of Daniel Simpkins’ The Lost Boys of Carbis Bay.

It’s not often you get a build-up and post-screening Q&A session that lasts longer than the film itself (it’s barely half an hour in full), but in no way were we short-changed, so to speak. And there are still chances to catch this indie wonder as it does its rounds, an initial six-venue tour format quickly expanded, both Friday screenings in the ‘Druth maxed out, followed by further January dates with Q&As in Newlyn, Bodmin, Saltash, Wadebridge, and Falmouth, then more this month, including those at the Flora in Helston tonight (Sat 14 Feb – sold out), The Ritz, Penzance tomorrow (Sun 15 Feb – limited tickets remaining) and the Phoenix at Falmouth (Wed 25 Feb – sold out).

Meanwhile, WTW Cinemas are screening the film on St Piran’s Day (Thu 5 Mar) at the Lighthouse in Newquay, the White River in St Austell, the Plaza in Truro (where there’s also a 15 Feb screening) and the Regal in Wadebridge, with tickets that day at £5 (see link for full details at the end of this feature).

The Lost Boys of Carbis Bay has already landed a Best Adventure & Exploration Film award at Kendal Mountain Festival, late last year, and I’d like to think there’s scope for a feature-length cut. However, as it is, it’s a winner – beautifully shot, with great lines and insight, plenty of heart, poignancy, and underlying positivity.

The general premise? We follow a group of ‘unlikely underground explorers’ as they go about their weekend hobby, visiting disused, historic tin mines, squeezing through tunnels, unearthing long forgotten and often frankly dangerous shafts, adits and hidden caverns, the viewer let in on their secret subterranean world.

I’m no potholing or climbing aficionado, but that’s only part of the premise. Don’t expect a po-faced documentary couched in designer mountaineering jargon, its know it all stars spouting competitive boasts regarding previous climbs and plunges. There are certainly highly competent climbers involved in the ranks of the so called Carbis Bay Crew, as is apparent when you hear ‘mine captain’ and main man Pat Moret talk about – with a fair amount of self-conscious understatement – past professional exploits and endeavours. But this is not some dry audio coaching video or – to the other extreme – adrenaline-packed boys’ own take on danger and derring-do (although there’s plenty of that).

It’s more about community and a sense of discovered purpose, connection and togetherness, the meat on the bones the personal stories and background subtly woven within, from a group that’s pulled off more than its fair share of heroic cliff rescues for dogs and caught out tourists.

I was lured in by the amazing locations involved, the rich history of those dank but spectacular locations and the generations of Cornishmen that worked there, and an ever-present wonder regarding what remains beneath our feet in a wondrous West Cornish land and seascape I can now claim as my own. And there’s lots of that on show here, even if the exact locations are often – understandably – not made clear.

What’s more, it’s lovely to see a film where you quickly warm to its characters – no mean feat when we’re talking a half-hour film. And they are characters for sure, a few of them present on opening night, answering questions down the front, post-screening, or – in the case of another who put in a starring role – hiding at the back (but not averse to a quick chat afterwards).

Hand on heart, I’m not likely to seek future invites on any of the Carbis Bay Crew’s adventures, however much I love what I see. A lack of head for heights and my beloved’s fear of enclosed spaces put paid to that. We’re the same when it comes to the rather compelling online videos from the fellow Celtic subterranean explorers responsible for the Ben o Cam online channel (Ben Dunstan and co, their videos often making for hairy ‘hide behind the sofa’ viewing, possessing the power to make us hyperventilate – and again, follow the link at the end for more detail). However, this was a cracking night in good company, neatly curated and introduced by the film’s executive producer, Kirsty Malcolm, representing Roll Nine. And it’s all rather inspirational and highly recommended.

All of which gave me a great excuse to track down the team behind the film, leading to a conversation with afore-mentioned director, Dan Simpkins, who prides himself in capturing ‘authenticity and emotion in every project,’ ensuring his cinematography ‘reflects the heart of the story’. So what’s he made of the public screenings and post-screen discussions so far?

“It’s been great. Whatever cinemas we’ve been to. Normally, Q and A’s burn out, and you have to wrap them up, but with this, people are so curious about the guys. It’s real fun touring it around Cornwall.”

Have the Carbis Bay Crew members joining you on stage at the end come into their own by the night, a little more sure of themselves in rather testing conditions )for a group who clearly didn’t set out to be screen stars)?

“Yeah, I think at first they were a bit like teenage boys. ‘I really don’t want to do this.’ You are putting them on a pedestal to be judged. But as it’s gone on – the more screenings they’ve gone – they’ve gained in confidence, seeing the film received well and that they’re presented well and people are fascinated by them. And now they’re properly cracking jokes too. A few times, I’ve been like, ‘Oh, it’s getting a bit borderline!’

“From a documentary perspective, it must be so weird that someone’s come in and put your story up on the screen. But each of them has kind of gone, ‘This is good’.”

I was relieved to discover this wasn’t just some thrill-seeking dynamic ‘in your face’ collection of mad camera work and extreme sport ‘rad’ images, cobbled together like a huge adrenaline rush or a parody within the parody of The Offroaders from The Fast Show. All the elements are there, but you deal with all that and manage to tell a poignant story within that limited time frame.

You also tackle the men’s mental health aspect, and for me this is more about the power of community and the friendship aspect between a gang of seemingly disparate, awkward blokes.

“Yeah, obviously there’s a part of me wanting to make this Netflix documentary with a huge climax. But the films I watch and that I’m interested in involve the nuances, and if you are making a film about an extreme sport, you have to do it from a personal angle – otherwise, the only people interested are those interested in that sport. So it was always important that we found the human angle, although I didn’t want to just do a film about mental health, because then it would be more charity led.”

Well, I didn’t find it a box-ticking experience.

“Exactly. With these guys I think I was worried initially that they may be self-aware of why they were doing it. It’s only through interviews that you sort of read between the lines and understand they’re doing it for a sense of community. They each have their own story, but the act of showing up for one another is what keeps them going.”

Out of interest, have you a head for heights? I’m guessing so, in relation to some of the cinematic moments.

“Heights never really bothered me, but I didn’t actually like going underground.”

That was my next question. Claustrophobia would seriously compromise your position here.

“When I was nine or ten, my parents took us to Wookey Hole, Somerset, and the tour guide started by saying there was a witch that lived underground, who could bring down the cave at any moment. Well, I burst into tears, it was horrendous!

“So I always had that in mind, not so much a phobia as a resolve to not go caving or go underground! But that was also part of the charm. I wanted to meet people who enjoyed doing that for fun.”

I only moved down 15 months ago but I’ve always been intrigued by what lies beneath, so to speak. Seeing some of the tight squeezes the likes of fellow caver BenOCam gets into only adds to that, following the tunnel networks around Cornwall’s once rich grounds for tin, copper, and so on. It’s all rather gripping… not least when it’s right under your doorstep. Add to all that the rain and storm-lashed winter we’ve just had – all those sinkholes and road collapses across the West Country. You become very aware of where you are.

“Yes, as Tim calls it, we’re like a Swiss cheese, full of holes. But what I find most crazy about Cornwall is that while there’s a certain amount that’s been charted, there are so many that have been lost to records, or new places being found. And they’re not all covered up, they’re just holes in the ground you can find. And I’ve been with these guys – it’s just incredible when you go down this hole and it just opens up into this chamber.”

It seems like you could easily get lost in the wrong hands. I get the jitters if there are left or right choices decided upon by pure instinct. Maybe you should unravel a ball of twine as you go.

“Yes, like Hansel and Gretel, having to leave breadcrumbs!”

On his website, Dan tells us he grew up by the sea in the South-West, where he ‘developed a love for the interplay between light and landscape,’ feeling that connection influences his work, ‘allowing me to adapt and use natural light and surroundings as key elements in storytelling.’

Whereabouts did he grow up?

“I’m in Cheltenham now, but I was born just outside the Cornish border. I lived in Bude, but was born in Barnstaple, as that was the nearest hospital. We moved around a lot – my dad’s a vicar – but we’ve always been South West based and always went on holidays to Cornwall. I also went to uni down in Cornwall. It’s the place I’ve spent the most amount of time, it feels like home, and I know it’s going to be the place I end up. But the industry is not in Cornwall… annoyingly.”

You clearly have your ear to ground for stories. How did you come across the tale of the Carbis Bay Crew?

“You’re always looking for inspiration, Cornwall is a big inspiration for me, and I’ve always been fascinated by the Cornish landscape. One summer, we went to Geevor’s tin mining museum, a tour guide showing us around this underground section. And as a filmmaker I felt, ‘This is really cinematic’. It’s really quite interesting, how the light bends, and it’s claustrophobic.

“We were like, ‘Oh, yeah, there could be a film here!’ I asked if there were any mine workings we could get to. {Award-winning Cornish director} Mark Jenkin had just done a video with Thom Yorke (for the Radiohead frontman’s The Smile project}, in an underground mine. I was very curious about it all, and the tour guide, so Cornish, tells me, ‘You don’t want to be doing that – don’t be like that Carbis Bay Crew lot!’ And you’re forever looking for ideas like that. I looked them up, found them on Facebook and reached out.

“What I found different about them is that there was so much personality and this sense of humour about them. And when I met them, they were exactly the same. They put themselves out on social media, but very much as themselves. There was so much life to them. I didn’t know where the film was going for a long time, so it was just about following instincts. I felt I just had to keep filming these guys. It was a passion project for a few years, me and a mate working in our bedrooms, editing together. and we find it so surreal, doing what we’re doing now!”

That’s Angus Breton, who shared editing duties with Tommaso Di Paola on the film. How did they get to know each other?

“We went to uni in Falmouth, living together for two years. We’ve been best mates since, and I ended up being his Best Man. We’re similar in personality, but also a little different, complementing each other quite well.”

I’m impressed how you get over the Carbis Bay Crew characters in a half-hour film.

“Well, we had so much footage, and there are so many other characters we could have focused on. It was almost more about the people who opened up to me. Tim was the first one where I was like, ‘Okay, I know what the film is now,’ the first to allow his time to be with me and be open. And when I left my job in London and moved down for two months to do this project, I was in the same village as Pat, so got to know him really well. He’s almost like a father figure to me now, just from sharing lifts and stuff like that. Most of the time, I wish I had a camera on me. It was those car journeys where he would randomly come up with something… and I find with men, they often have to be doing something else to speak openly in front of you.

“Benji was the only one where I was like, ‘I want to film you!’ He was the most chaotic. And I actually thought I’d finished filming when Paul reached out with his story, which is the emotional crux of the film. So I think it was just about trust – they had to know I was going to do them justice. And there were lots of strands where I started filming but it didn’t quite come off.”

There’s clearly a feature length film here… if you had the financial backing.

“That’s the thing with passion projects, especially documentary – so much is self-funded. I work on set a lot, but I’m proven as a documentary filmmaker. You have to earn your stripes before you even think about funding. And I’ve never really liked being told what I can or can’t do!”

So Jeff Bezos hasn’t yet pulled the plug on Trump and offered you 75 million to promote a film?

“Not yet, but we are trying our best to try and get it out there. We’ve independently distributed it. We’re all in full-time work, but any spare moment we’re typing emails and stuff like that.”

So who are Roll Nine, the company behind the film?

“Roll Nine is ran by Kirsty Malcolm, who I met when I left uni, working on a lot of editing work with her and Angus. They were really nice and when everyone was saying no to us, Kirsty put out on her Instagram account that she was looking for more adventure documentaries and stuff more in her interest. So it was almost like it was meant to be.

“She believed in the project where no one else did, really helping with advice, then eventually put money in to help complete the film. Kirsty’s done our PR as well, which allowed me to do all the cinema stuff. We owe a lot to her.”

Rewatching the trailer this morning, I was reminded of the illuminated underground bike scene. Was that just a filmmaker’s folly?

“They had the idea already. There’s this one mine – and with the Carbis Bay Crew, they’re very careful not to name them – where there’s this big open chamber with a track running all the way through. It was a passing comment that it would be fun to ride bikes down there. I don’t think they would have done it, but I heard that and felt that sounded like an ending. And yes, attaching the lights was a filmmaker’s flourish! It’s kind of surreal, but rooted in reality, and I’d hope it sort of creates a deeper meaning.”

And how did this 28-year-old rising star get into all this (his CV including some impressive short films, documentaries, commercials and pop videos so far – see link below)? The first I saw was something of a family affair, following life on his uncle’s farm, his cousin Jeff the star.

“That was my first attempt at shooting a documentary, independently, around three years ago. I worked for a camera rental company, going out testing new lenses so they could promote them online. I filmed my cousin one day, really liked the footage, and turned it into a 90-second document. And it won a Canon competition. Being from a working-class background, I never had money for my own camera, so winning that actually gave me the camera that allowed me to quit my job and keep filming.

“I’ve always been driven. As soon as I found film could be a career, I was always like, ‘This is what I want to do.’ But I’ve always wanted to do it in my own way.”

As well as the ongoing screenings for The Lost Boys of Carbis Bay, Dan’s also promoting a shorts programme, with more than a dozen screenings, running with two other films, described them as ‘very much feelgood outdoor films’. In that case, The Lost Boys of Carbis Bay has support from Hansel Rodrigues’ King Putt and Joel Porter and Alex Moore’s Frankenbiking, initially running at Halwyn, Crantock, Newquay (Thu 19 Feb) and the Regal in Redruth, the Savoy in Penzance, the Capitol in Bodmin and the Phoenix at Falmouth (all on Wed 25 Feb), the organisers promising a night celebrating ‘ordinary people doing extraordinary things’, from the world of custom biking to professional crazy golf.

And then what, Dan?

“Our next step is trying to find a platform for this film, maybe the BBC or National Geographic, something along those lines, so it’s seen beyond the cinema.”

I could see that. It’s prime BBC Four or Sky Arts territory, I’d say.

“Yeah, that’s our aim now – distribution. And that our films get funded so it’s not out of our pockets. We’ve never had big chunks of money, it’s always just chipping away where we can.”

All stills photography copyright of Daniel Simpkins and the Carbis Bay Crew’s Tim Clarke, used with permission.

For an up-to-date list of screenings and tie-in events, follow this link. There’s a further link to a promo trailer for The Lost Boys of Carbis Bay here, and you can find out more about the Carbis Bay Crew via their Facebook page. Dan’s own website is here, and while you’re at it, I recommend the BenoCam video channel (with a Facebook link here).