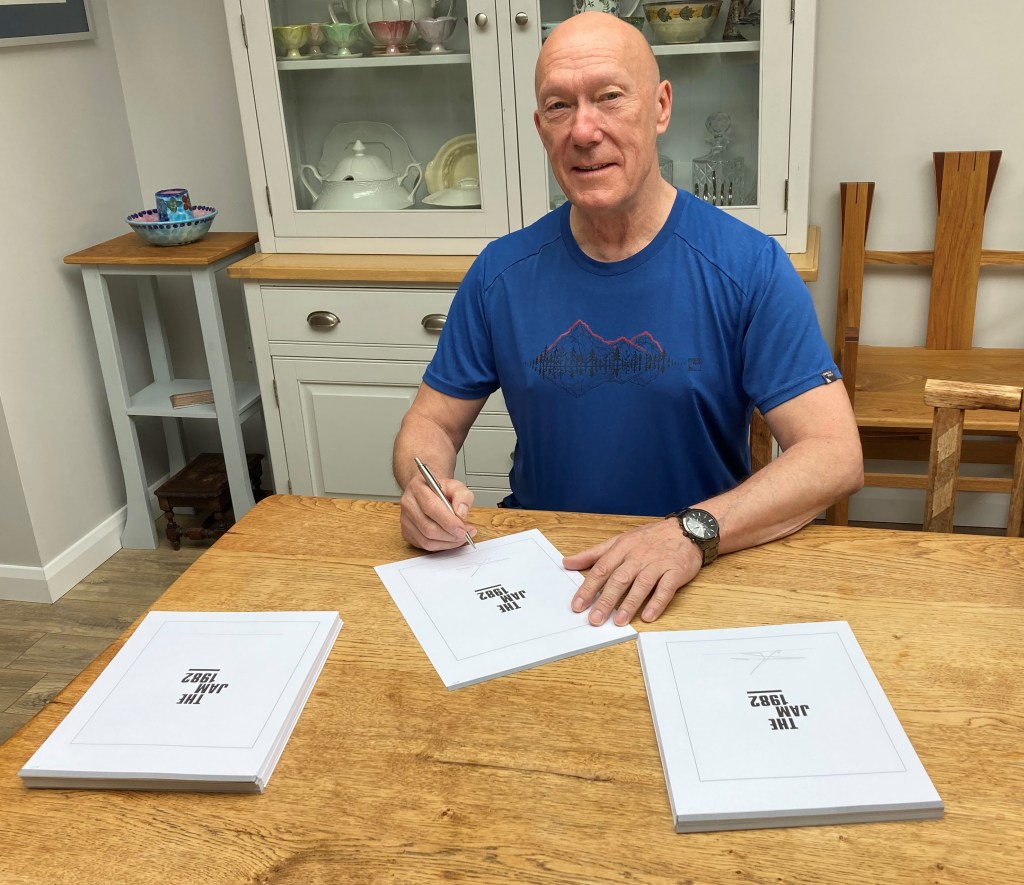

This time 40 years ago, Rick Buckler must have been wondering just what was next, Christmas and New Year behind him, the ultra-successful group that had been his life for the past decade disbanded, his future uncertain. But as the wording on the back of a new book he’s co-written about The Jam’s final year puts it, ‘It was the end of an era, the start of a legacy’.

The Jam 1982, written with respected music writer Zoë Howe, tells the story of the final year of one of the most iconic UK bands, a tumultuous 12 months that ended with front-man Paul Weller controversially calling time on a three-piece he co-founded a decade earlier, having gone on to amass four UK No.1 and 18 top-40 singles, plus five top-10 LPs by the time that year was out.

As The Jam, Paul (guitar, vocals), Rick (drums) and Bruce Foxton (bass) spearheaded a late ‘70s Mod revival and before that rode the wave of punk, yet always forged their own path, continuing to move forward, their tight live shows, razor-sharp style and perfectly-crafted songs earning a hugely deserved and devoted following.

By 1982 they were bigger than ever, but the pressure of success was taking its toll, Paul’s shock decision – taken at the peak of their powers – far from welcomed by his bandmates, let alone fans.

The Jam 1982 is a neatly compiled, richly illustrated, full colour, 176-page glossy hardback recalling that momentous period – ‘eye of the storm stories of life in and around The Jam from the recording of The Gift just before Christmas 1981 through to the end of that following fateful and unforgettable year’ – and includes previously unseen images (some from Rick’s own collection) and untold stories, in a revealing oral history taking us from the recording and release of final studio album, The Gift, to their last appearances together.

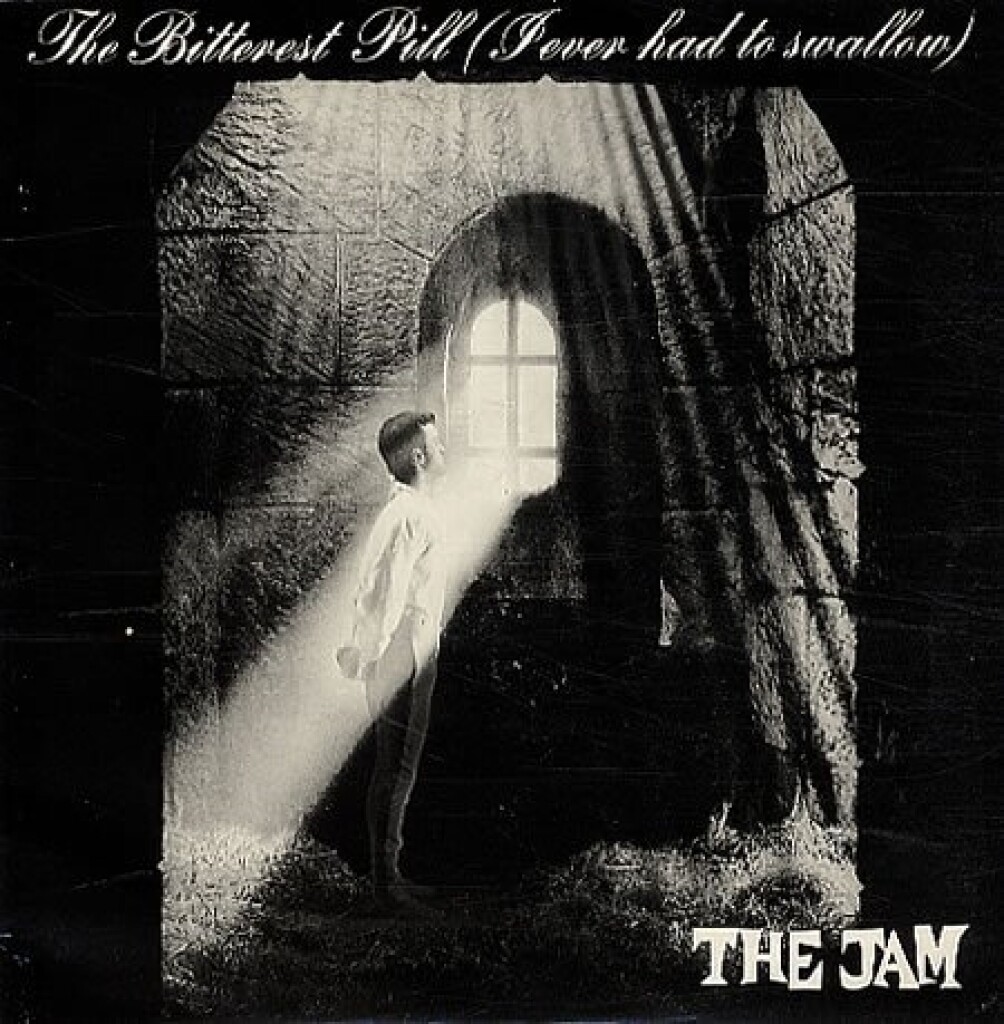

In addition to Rick’s memories and excerpts from various print and broadcast media interviews, including several with Paul and Bruce, The Jam 1982 brings together testimonies from the likes of broadcaster Gary Crowley, producer Peter Wilson, A&R manager Dennis Munday, music publisher Bryan Morrison, photographers Neil ‘Twink’ Tinning and Pennie Smith, music writers Paolo Hewitt, Mark Ellen, Chris Salewicz and Valerie Siebert, Big Country drummer Mark Brzezicki (later Rick’s replacement in From The Jam), Suede bassist Mat Osman, singers Jennie Matthias (Belle Stars, who sang on ‘The Bitterest Pill’) and Tracie Young, touring musicians Jamie Telford (keyboards) and Steve Nichol (trumpet), plus Paul’s sister Nicky Weller and dad John, the legendary Jam manager, all helping put a new spin on the tale of the fateful year three Woking class heroes went out at the very top of their game.

I shouldn’t need to go into the full history, but Rick gives us his take on the early days in the book’s introduction, telling us, ‘From the moment I teamed up with Paul at school to start a band, everything else became secondary. We started out as a three-piece with Steve Brookes on lead guitar and vocals, Paul on his prized Hofner violin bass and backing vocals, and myself on drums. We also had a name – not a very good name we thought – but it would do until we thought of a better one: The Jam.

‘Dave Waller joined on rhythm guitar, learning to play on the way. Rehearsing in Paul’s bedroom we got together a set of ‘60s covers and put on an hour of music as we worked towards our first gigs in Sheerwater Youth Club, county fairs, and anywhere around the Woking area we could secure bookings. Dave soon dropped out, but we continued to go out as a three-piece, improving our set and adding some rather dodgy self-penned love songs along the way.”

In time, Steve left and Bruce joined on bass, while Paul switched to guitar, history in the making, even though it would be 1977 before it all truly came together. But while much has been written about the full tale, Rick felt, four decades on, ‘The real inside story hasn’t been fully told,’ adding ‘The Jam still means a great deal to me and so many others. I’ve always thought it was a great shame that we did not take it as far as we should.’

And as I put it to him, this latest Omnibus Press publication makes for an impressive read, a welcome addition to an already mighty canon of books about the band.

“Yeah, I think the publisher did a good job on laying it out, helped by having access to a set of photographs, which we expanded on. And those photographs tell a lot more about the story at the time. Because it was a decisive year, for all sorts of reasons.”

There’s an understatement if ever there was one, Rick realising that and laughing as the words slipped out. And a lot of those images, including the front and back cover shots, were by ‘Twink’ Tinning, and while I – like so many of us – already knew a fair bit of the story of that decisive final year, I was intrigued by Rick’s take on how his photographer friend came into the band’s confidence and into a position where he could get such close access. For his pictures certainly tell part of that tale.

“They do. Most of the photographs of the band up to 1981 were fairly staged, and normally always associated with us being interviewed. The whole thing was a little one-sided. But I said to the guys about this good friend of mine, Twink, and said let’s take him on the road, so he came along with us on tour, taking shots other photographers simply didn’t have access to.

“And it turned out to be a really good thing. Unfortunately, they were rejected by {Paul’s father, and the band’s manager} John Weller right at the end. He refused to pay Twink, who held on to the rights of those photographs, and a lot of them never got seen. But I always thought he was a really great photographer, as seen on those cover shots, and there’s loads of the audience, like those taken from behind my kit.”

There are certainly some candid pics among them, and on one that springs to minds it looks like Paul’s about to rip Twink’s head off for snapping him and his girlfriend at the time, Gill.

“Ha! Yeah, especially with that one – they’d just fallen out, and weren’t speaking to each other. Paul’s looking one way, Gill the other, and that sort of thing used to happen on a regular basis. Twink would just walk onto the bus and take a photograph. There was real spontaneity, and I suppose there’s a bit of an insight into what was going on.”

At the same time, I’m pleased to hear that Rick and his partner at the time, Lesley, another caught on camera within, remain an item all these years on. Hardly the rock’n’roll way, mind.

“Ha! Yes. Absolutely. Unbelievable, isn’t it?”

Perhaps Rick just got out of the big, bad music business at the right time … not as if he saw it that way at the time. He met Lesley, also from the Woking area, in 1978, coming up to 45 years ago (“I know. It’s frightening. The joke is, you get less for murder!”) and they still live ‘on the edge of Woking’, all these years on.

As the cliche goes, I bet they’ve seen some changes. My nan, and before that my dad and grandad, lived at the Maybury end of Woking. And even back in the ‘80s she’d tell me on weekend visits to ours, ‘I hardly recognise the place, it’s changing so much. They’re pulling everything down.’

“Yeah, I think like all those remote towns, seeing it evolve from after the war, where they were knocking a lot of it down, to the regeneration of town centres. And it is completely different to what it used to be 40 years ago.”

When I walk away from Kingfield after the football these days, I’m met by the sight of all those massive high-rises in the town centre, wondering if I’ve stumbled into Beijing somehow.

“Yeah, I don’t know, some people like them. I’m not sure about them really, but they’ve got plans for more. It’s certainly changed.”

The new book is dedicated to respected music writer Simon Wells, who was working on this project ahead of his illness. Sadly, he died after a battle with cancer in 2022. Did you get to know him?

“I bumped into him a few times. I didn’t know him too well. He was put forward by Omnibus to help do a lot of the research. Unfortunately, we hadn’t really got started before he was diagnosed. He said, ‘We’ll get together once I’ve been in hospital and got this thing sorted, then we’ll get stuck into it.’ Sadly, we never really got started. Yeah, it was very sad, and I was quite shocked at how quickly it took hold.”

Accordingly, publication times came and went, before Zoë stepped up to take the project on, another revered writer with a wealth of previous acclaimed music biographies behind her, past publishing projects including biographies of Lee Brilleaux, Poly Styrene, Wilko Johnson, Florence + the Machine, Stevie Nicks, The Jesus and Mary Chain, and The Slits. She knows her stuff, and she’s done a great job with you here.

“Yeah, it was a bit strange, because we did most of it at a distance. But she helped out a great deal, doing a lot of the interviews, phoning people up, typing it up, what have you. I’d not worked with her before, but she has a lot of experience with other books.”

Perhaps it helps that she knows how to deal with drummers, I joked, being married to Dylan Howe, from Wilko Johnson’s band.

“Absolutely! She knows the music industry, and we rubbed along alright there.”

Gary Crowley writes in the book’s foreword about a life-affirming Battersea Town Hall date in late June 1977, his first live gig, aged 15, recalling, ‘Paul and Bruce jumped around the stage like synchronised trampolinists plugged into the National Grid whilst Rick sat steady at the back, pounding the skins on that jet-black kit, cool as fuck in those Roger McGuinn shades, keeping the solid beat which underpinned their revolutionary sound and led the charge of their musical attack.” And for me, he sums up the spirit that fans saw in the band, that ‘fire and skill’ we often hear about. As with The Clash, and the likes of Mott the Hoople before, there are plenty of tales of kids being let into pre-show soundchecks. There was a real affinity with fans, I suggested to Rick.

“Yes, a lot of that came from the very early days when we were playing the clubs. A lot of people twigged that if they got there in the afternoon, especially London shows and pubs, we’d be doing soundchecks at about three or four o’clock. They’d come along, get stuff signed, and just talk to us.

“This was prior to us getting signed. And the first thing we did with the record company was sort a tour, which involved only London – the Red Cow, the Nashville, the Marquee, those sorts of places. John {Weller} wasn’t particularly keen on it. But it was something we did and carried on through to playing the larger shows.”

In my experience, I’d say that remained the case long after the split, and it was in late 2007 that I first saw Bruce and Rick, by then with From the Jam, having the pleasure of a backstage audience with the band at Preston’s 53 Degrees university venue. In fact, I recall Rick taking me to task – somewhat bewildered, perhaps – on my then-regular 500 mile round-trips to watch Woking FC home games, despite so much football competition on my adopted Lancashire patch. Meanwhile, there was Bruce, who I’d chatted with earlier, patiently waiting to get a word in so he could say goodbye and get back to his hotel, both equally generous with their time.

It’s been a while now since Rick stepped away from that live line-up. No regrets? Was that a good time to end that chapter of his career and concentrate on his writing and Q&A commitments?

“From the Jam? Well, yeah, it became hard work. It was great, because I really wanted to revisit the songs. And we did, but when Bruce came on board, unfortunately, he took a completely different take on things. I didn’t really want to go down the road of becoming a tribute band, going round and round doing the same old thing.

“Myself and {keyboard player} Dave Moore did try to get into doing new material, and the view from Bruce at the time was that if we did, we’d be shooting ourselves in the foot and wouldn’t be able to pull an audience, because they’d only be there for the Jam material, which was fairly true.

“I thought, you know what, it just isn’t working anymore. We weren’t earning any money, all the money we were earning spent on ridiculous things like hotels. You think, ‘I’ve run this, it’s done its course.’ I wasn’t there to support anybody’s ego or what have you. I felt, ‘I don’t need this.’ So I left, and that was that.

“I did a couple of other things later, getting together with Ian Whitewood from Sham 69, a two-drummer thing there. Then I did the autobiography, and that was coming on for six or seven years. So yeah, I think one of the biggest things in the music industry is never to become boring. And I think From the Jam had become a bit boring, and it wasn’t really working for me anymore.”

I take your point, but since then we’ve had a couple of cracking Foxton & Hastings albums outside the live show format, with Bruce and singer/guitarist Russell Hastings (who co-founded the original band, The Gift, with Rick and Dave Moore in late 2005, Bruce joining earlier in the year I first saw them) writing their own material. Very good they are too … as are the live shows. So perhaps Bruce was willing to take that suggestion up after all.

“Well, yeah, the penny finally dropped, I think. But there were lots of tribute bands out there playing Jam stuff {at the time}.”

Only one with a genuine Jam member involved though. Anyway, I didn’t dwell on all that. Instead, I headed further back into the memory banks, picking Rick up on his assertion that there was determination and dedication from the moment The Jam formed at school. Clearly the belief was always there, and they were all very driven, doing their apprenticeship of sorts in pubs and clubs, mostly playing covers at first, largely on the South-East circuit, but gradually adding more and more of their own songs, before that move up to London to take it to the next level. Was there a day that Paul or fellow founder member Steve Brookes turned up with a song and you thought, ‘We’ve really got something here’? Did you hear, for example, ‘I Got by in Time’ and think, ‘yes, we’re on the right track!’?

“I don’t know. It’s difficult from the inside to judge that, but one thing I remember that we did know, but weren’t really sort of facing up to, was the fact that most of the songs written in the early days were love songs, our influences really coming from us being a covers band, so we thought that was okay. But it really wasn’t enough.

“When we encountered what was going on in London, the pub rock scene, and saw all these other bands, that sort of broadened our horizons. It was becoming boring, doing the same thing over and over, but we had the foresight to say we wanted to go and play the London scene.

“Unfortunately, from John’s point of view, that wasn’t a good idea. Because we weren’t going to get paid. A lot of the band were doing it for the love of it, not the money. John didn’t like that at all. From his point of view, we had to borrow a van, there were petrol costs, all that sort of thing. So we came up against a little bit of opposition. But if we weren’t going to be doing the clubs, and we were going to play in London, I don’t think he had much of a choice into anything but going along with it.”

As you point out in the book, as a band you never rested on your laurels. Every LP saw The Jam move forward. And yet you’ve had four decades to ponder over all that now, and accordingly come over as rather philosophical in print on the consequences of Paul’s decision to end it. I wonder if you truly felt that way at the time. I recall bitterness within the ranks when Paul called time on The Jam when he did, yet you seem to convey a more laid-back inevitability now that he was unlikely to change his mind.

“Well, yeah, absolutely. I don’t think there was ever any bitterness as such though. We were grown up enough to sort of accept the decision that Paul wanted to leave the band. Where the bemusement came, let’s say, was the fact that we didn’t really understand his reasons. Having known Paul, and that he can be a bit kneejerk at times, over his reaction to things, we thought, ‘One minute you’re saying this, the next you’re saying something else.’ Then when he was free of having to look us in the face, the reasons changed again.

“I didn’t mind whatever his reasons were. It just became a little hypocritical that he said to us one of the reasons he wanted to leave was because he was on a treadmill. But he’d already signed another treadmill deal with Polydor before our last show. That didn’t make sense.

“I really think there was more going on in the background. I think a lot of it was to do with the way John managed the band. We were beginning to ask questions, like, ‘Why aren’t we earning any money, John? Why are you going around saying Paul is now a millionaire?’ I couldn’t afford to buy a car. Those sorts of questions were beginning to raise their head.

“I’m not being funny, but I really think that was probably a contributing factor as to why Paul jumped ship before … I think that had a lot to do with the demise of the band, which was a real shame, because things were creeping in that weren’t anything to do with us, musically. It was to do with things like the money and the fame, which becomes a vacuous reason to throw things away.

“There were other things as well, and we always got the feeling that Paul didn’t like touring America. And we were getting to the point where we were probably going to have to start doing very large shows. The last shows we did were like the Wembley ones – multiple nights at the same venue.”

There’s a lovely quote from you in the book where you contemplate, on that matter, ‘Maybe we should split up more often.’

“Ha! We could easily have done a worldwide tour as a last thing, ran it right into 1983. But …”

There was a school of thought that maybe you could have just taken a break, then possibly come back again, refreshed.

“Well, that’s right, but there seemed to be a sort of rush from Paul to get it done. And there always seemed to be another reason why such a decision was made. The last shows were great. Anybody who went to those will know we still gave it 100%. We were still doing really well, the record company happy because the records were still selling. All the fairy stories in the world about trying to make the band mean something – complete twaddle. The band absolutely already meant something, and to so many people. The reasons for it just seemed vacuous.”

With that in mind, I wonder what a seventh Jam album might have sounded like. Would it have been anything like the first Style Council album? A few of those songs were demo’d, like ‘Speak Like a Child’.

“Yeah, we already had stuff rehearsed, if not recorded, that we were going to move forward. But I don’t think we would have ended up like The Style Council. The songs might have gone down a different route … which was always the way.

“I’m no fan of The Style Council. It all seemed very sort of one-man band. The production I didn’t think was particularly good. Bruce summed it up to me when we met up, as we often did during the ‘80s. He said one day, ‘If The Jam had evolved into The Style Council, I would have left.’ That’s always one thing that’s bemused me. Why throw away The Jam for what The Style Council would become? No one had a crystal ball, but it seemed very odd.”

Paul has always punctuated his career around such moves though. Most work, but some don’t (and fair play to him for that, as far as I’m concerned). In a sense, I see that period (and I should stress that I enjoyed various aspects of The Style Council, who left us with some great songs, LPs, and memories, and surely Mick Talbot deserves credit there too) as the beginning of his solo career, taking himself somewhere different.

“It was really, if you look at it in the cold light of day, I don’t think The Style Council were regarded as a band. It was all very much a solo project, which also sort of begs the question … I don’t know if he was just trying to be more in charge of the way everything went.

“Anybody who was in a band that became successful will tell you, your life is not your own. Despite the way you might want it to turn out, you always have to step up to the mark as far as commitments that you make towards touring, recording, et cetera. If he thought that was the reason why, I think that was delusional. I don’t think that was going to be the case.”

Then again, so few great bands survive as a creative machine beyond a decade (and in The Jam’s case, they had five years as a bona fide recording success) and retain their fire. And you had lived in each other’s pockets for a fair bit of that 10-year tenure. Or had you? Because by that stage, Paul had been up in London for a long time, and it seems that yourself and Bruce were happy to do day-trips up to town to work on new material. Were you, Bruce, and Paul, very much your own people by then? The days of piling into the back of a van seemed to have been way behind you.

“Well, yes, Paul was the only one who could actually afford to live in London. He was paying more money in rent, probably twice as much, than I was on my first mortgage in Woking. We simply couldn’t afford it, if we wanted to or not. But we did everything we possibly could.

“The record company knew there was pressure on Paul, so we would always record in London – never outside the capital, at a time when people were mostly going to …”

Studios like The Manor in Oxfordshire?

“Exactly. We did all sorts of things to alleviate that, so Paul could be home for tea. I know that sounds funny, but that was the way, and we were quite up to accommodating that. And Woking is actually not that far … I got ribbed by Paul for having a mortgage. Really? Wouldn’t I love to be able to rent a little place in Pimlico! I simply couldn’t afford it.”

And recording in London is surely no bad thing if, for example, Paul McCartney is in the next studio (making Tug of War). Was that another of those ‘where did it all go wrong’ moments?

“Ha! The thing is that I don’t have any regrets over what The Jam did and what we achieved, and all the things that led to it. One thing I wonder about at times is that I think sometimes Paul forgets that everything that happened to all three of us all stemmed from the work we did as The Jam.

“That established us within the music industry. Everything that happened afterwards was because of The Jam. Myself and Bruce used to think, ‘Why is it that Paul won’t play Jam records when he does a radio interview or in his live set?’ There was a period of around 15 years where every time I went into a radio station, one of the things people used to almost pull me up about was, ‘Why when we interview Paul won’t he talk about The Jam?’ But I think one of the reasons was likely what we’ve already spoken about.”

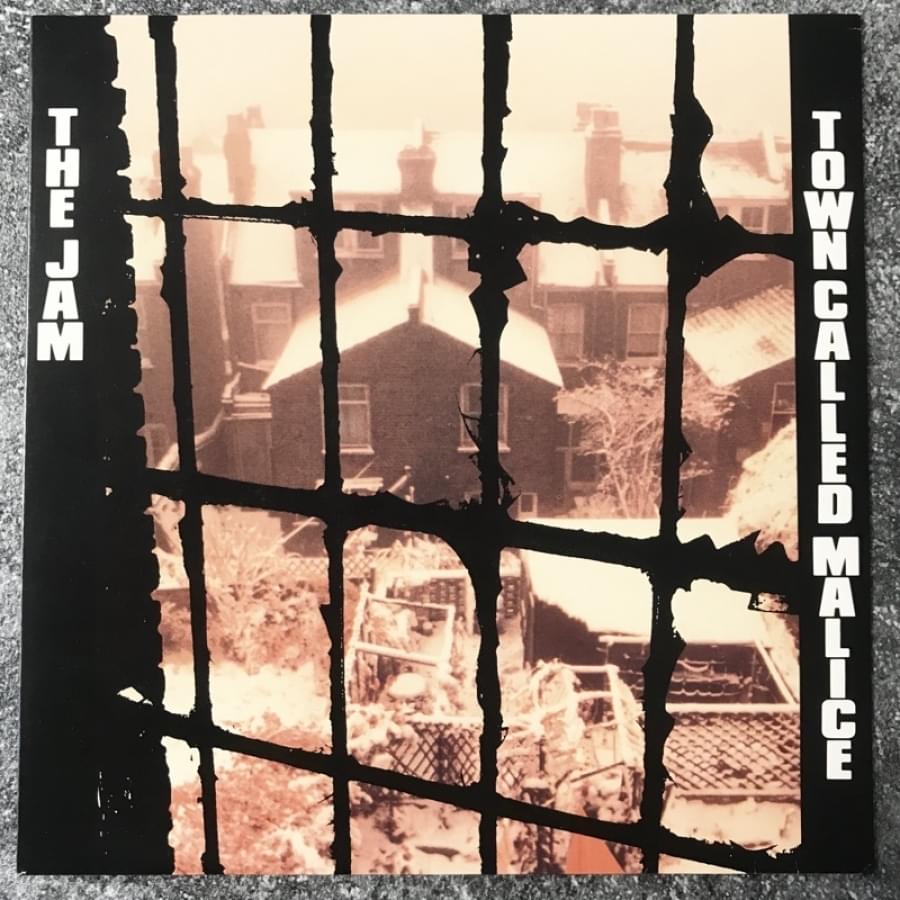

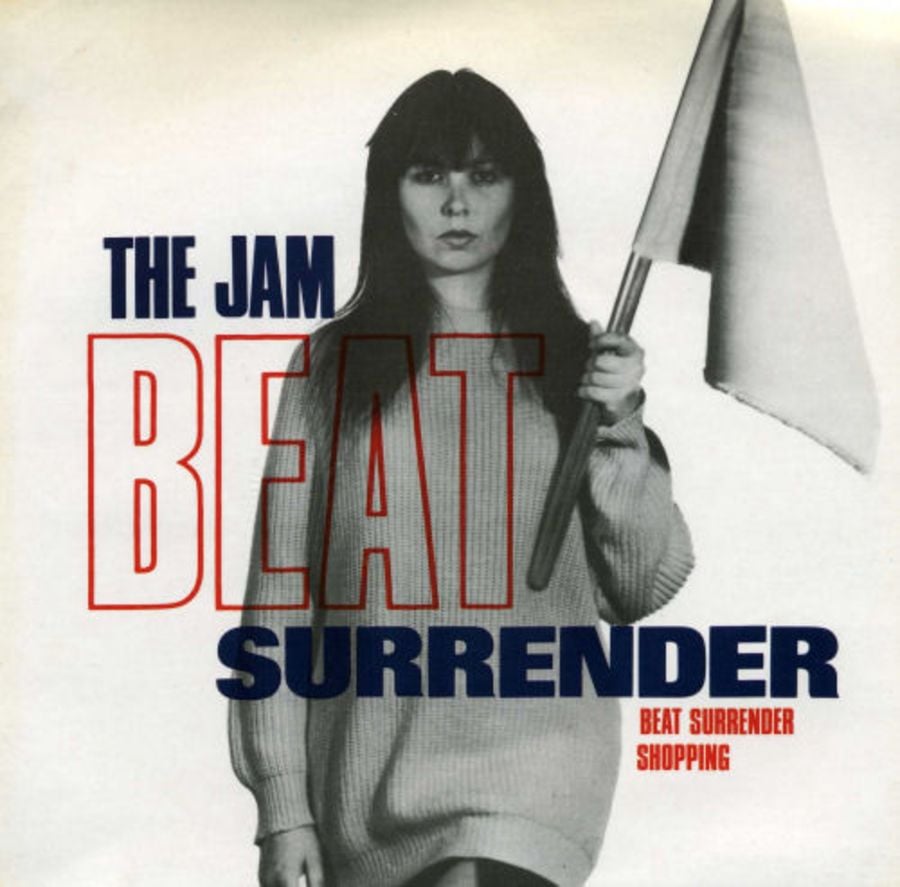

Once that fateful decision was made about splitting, you and Bruce – at least outwardly – seemed to keep your head down, getting on with the job. The professionalism continued. And in a year when you’d already made a classic single like ‘A Town Called Malice’ and given us The Gift, which carried so many great tracks (I’ve been replaying it in the car recently, and it still grabs me), there was still ‘The Bitterest Pill’ and, wow, ‘Beat Surrender’ to come. What a way to go out, and 40 years on still sounds so sharp.

“Yes, it does. I find that quite amazing, the longevity of everything. Which, you know, we didn’t sort of plan for, because I don’t think you can. I just think we must have been doing something right at the time for that to be the case. So that’s something for all of us to be very proud of.”

As a Guildford boy, born at the Jarvis Maternity Home on the edge of town, that Surrey borough my base for the first 25-plus years of my life, it’s a point of pride that I’ve heard it said many times in band and fan circles that your Civic Hall show – the penultimate Jam date – was the proper farewell, with the Brighton finale that followed comparatively rather flat, at least emotionally. I was just shy of 15 when the split announcement came, and although I tried to get tickets for that and The Gift tour before, I had no chance, missing out on that big moment on my patch. But it seemed like that was the big night.

“Well, yeah, quite early on, we realised where we did the last show was going to be of some importance. Initially it was going to be the Guildford Civic, but for one reason or another we couldn’t do multiple nights there, and as soon as we put shows up for sale, they’d be gone, almost overnight.

“The same thing happened with Wembley in the end. We had to say, ‘Stop, we can’t keep adding nights on!’ It was getting ridiculous. Brighton was no real home for The Jam. It was just this sort of frenzy for the Mod thing, the fights on the beach from the 1960s … which in itself didn’t really exist. It was all a bit out there, really. But it was a good place to play, and a fairly large venue.”

Incidentally, putting you on the spot, do you remember your first gig in Guildford?

“Well, I tell you what, we played a club on the same night Guildford got bombed. …”

Indeed. October 5th, 1974 (when two IRA bombs were detonated at different pubs across the town, around half eight to nine in the evening). That was the one I was thinking of.

“I’m trying to think of one earlier. I’m not sure whether there was. And I’m trying to think of the name of the club …”

Bunters. Close to the A281 road heading to Shalford, my home village.

“That’s it! We were supporting Rock Island Line. Their claim to fame was they were in That’ll Be the Day. They were a real sort of Teddy Boy band. We didn’t actually get to play the gig, unfortunately. The bomb{s} went off, and everything got closed down, so it was our first non-gig!”

I was three weeks short of my seventh birthday then. I was packed off to bed that Saturday night, but remember one of the blasts. I thought someone had slammed the airing cupboard door on the landing. That’s how loud it was, two miles down the road. Soon, my dad was tuned in to police radio, as was often the case, everyone listening in downstairs. My older sister and grandad were planning to go for a drink in town, but as it turned out they decided to stop at the village hall social club … not as if we knew. Thankfully they stayed put. Did you hear a blast?

“No. I remember we set up the equipment in there, went home to Woking, had some tea, because we weren’t going to be on until really late at night. But then we got a phone call, saying we can’t come back because they’d literally shut the whole of Guildford down. So we were a good seven or eight miles away. But yeah, it was a devastating blast.”

Incidentally, a later background check, online, reveals The Jam did play Bunter’s before that ill-fated date, possibly appearing there twice in July ’74, in the days when they were Michael’s Club regulars in their own hometown. And moving forward to 40 years ago, January 1983, the festive season well and truly over, the reality of the split having truly sunk in, Rick no doubt thinking, ‘What am I going to do now?’, could he remind me of the timeline from there? Did his spell in Time UK follow more or less straight away? Was he on with that before ‘Speak Like a Child’ charted in March?

“As far as I can remember, I was the first member to get back out on the road. I was probably quick off the mark. I found a songwriter, Jimmy Edwards, and we were soon rehearsing, and on the road quite quick, because that was really what I wanted to do. And I remember going to see Bruce later that year when he did his solo thing.”

Well, I did manage to get tickets that time, when Bruce toured his Touch Sensitive show and visited Guildford Civic in May 1984.

“It was a difficult time. Like the music industry still, I assume, the style of things was changing quite quick. Punk had already died out, other bands were coming in. If you look at the chart in 1982, when ‘Eye of the Tiger’ was No. 1 {keeping ‘The Bitterest Pill’ off the top, criminally}, I felt quite good that The Jam was still in there. We were doing well in the charts, even though a lot of the punk bands were not. And in 1983, I don’t think it was a particularly great year for music, but it was certainly changing.”

There was a brief band reunion with Bruce around that period too, the pair forming Sharp with the afore-mentioned Jimmy Edwards, recording for the short-lived Unicorn label, subsequently reissued on a Time UK anthology. Did Rick keep in touch with Jimmy Edwards?

“Yes, absolutely.”

Jimmy Edwards died in early 2015, aged 65, after battling cancer, while Time UK bandmates Ray Simone and Danny Kustow (the latter best known for the Tom Robinson Band) have also passed away.

And getting back to those early days of The Jam, has Rick spoken in recent years to co-founder Steve Brookes?

“No, not really. I mean, it was the typical story when he left. And crikey, that was very early on. I think he just fell out of Paul’s bubble. Paul just stopped seeing him.”

Something of a precursor to what was going to happen later, I suppose.

“It was a bit. I don’t think he spoke to him for 30 years or something. That was a bit of a shame. But I do bump into him now and again, around Woking. The last time I saw him was in a pub near me. Yeah, he’s okay. I think he’s still going out as an acoustic player.”

Absolutely. I saw him at the Boileroom in Guildford, supporting Stone Foundation in late 2021, and he was great. He’s certainly a gifted player.

“Well, yeah. At the time, when we were still at school, Steve was the lead guitarist and the lead singer, and Paul was then on bass ….”

And Steve was on grand piano, quite literally, at a show at Woking Conservative Club, I understand (during a cover of ‘Johnny B. Goode’, ending up being ‘chased from one side to the other in an attempt to stop him scratching the polished surface’).

“He was, yeah! I’ve still got memories of that. That was quite funny. And I don’t think we cared too much whether we went back and played there again! Ha!”

Pleased to hear it. And I’ll not even bother asking if there’s been any reunion with Paul, because we’ve been there, and I don’t think you’ll suddenly say, ‘Actually, I met him last week and we’re buddies again…’

“Ha! Well, I will say one thing, which I don’t really understand … at the time, and still, we never actually fell out. There was a time when Paul was putting it about that we weren’t even friends. I don’t know where that came from. It was always a strange thing that people often think that we sort of fell out at the time. Another reason that didn’t seem to make sense.

“It’s just part of Paul’s make-up that once you fall out of his bubble, that’s it. We saw it happen with girlfriends, Steve, all sorts of people really. He doesn’t seem to have that mentality to stay in touch with people.”

I should add that Steve has also worked again with Paul in recent years, and while you don’t really need my opinion, despite any bad feeling or bewilderment over how it ended, Paul ultimately made the right decision, however skewed you could argue his voiced reasons were for doing so. The Jam ended on a high, and that’s something to be commended. I’ll have the last word here too (it is my website, after all), adding that with so many bands I love, not just The Jam, I always want to say, forget all that fall-out crap, make up, and put aside any petty arguments. I know Bruce and Paul made up again, so part of me hopes the same happens with all three. Just have a big hug and get over it, lads. If the last few years have taught us anything, surely life’s too short. And The Jam have, as Rick put it, so much to feel collectively proud of.

For this website’s February 2018 feature/interview with Rick Buckler, head here. And for our April 2015 conversation, head here.

For more about The Jam 1982, head to https://omnibuspress.com/. A signed, limited edition version, including an exclusive print, is also available. And for Rick Buckler’s upcoming live Q&A dates, try http://www.thejamfan.net/. You can also check out https://www.strangetown.net/.