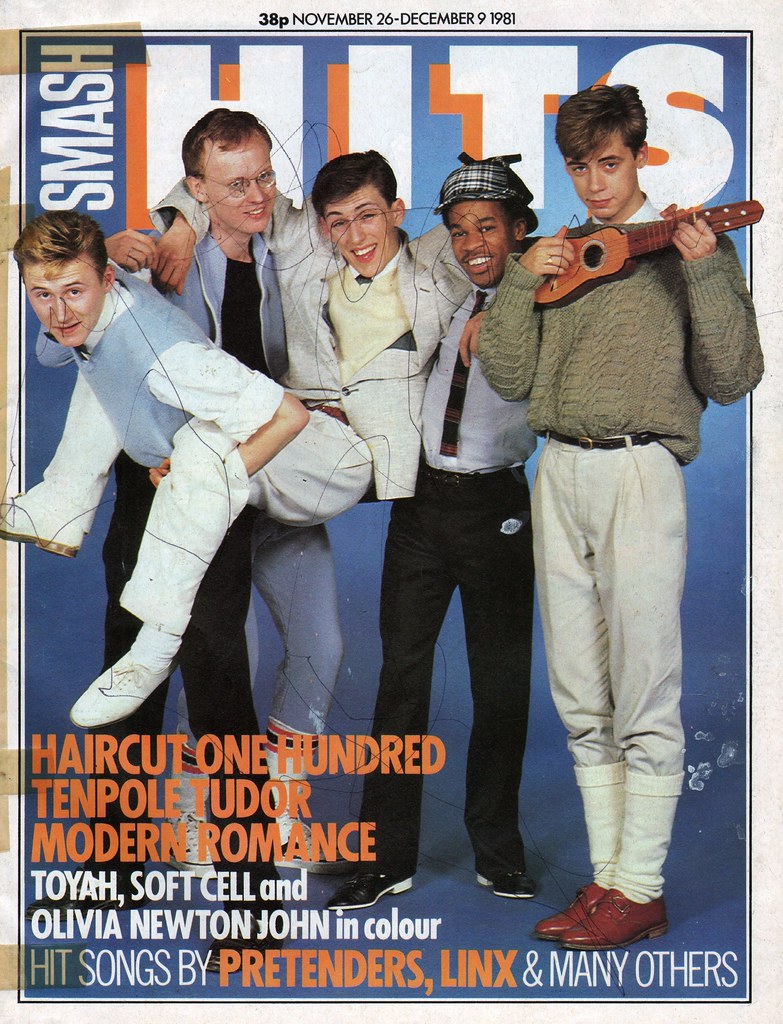

Haircut One Hundred are back, celebrating their 40th anniversary with a live show and special edition of Pelican West, the debut LP that saw them on their way all those years ago.

And that was all I needed by way of an excuse to get back in touch with guitarist Graham Jones, who left London for Cornwall in 1990 but is very excited about a 2023 Shepherd’s Bush Empire show that sold out in a matter of days.

But before we get on to that, let’s go right back, Nick Heyward (guitar, vocals) and Les Nemes (bass) setting the ball rolling as early as 1977, although it was only after they relocated from Beckenham, Kent, to central London that Graham (guitar) came on board, the band soon adopting its distinctive name.

“The old story we keep trawling out is that our girlfriends, who were best mates, were the connection. Nick and Les were already doing this band, Moving England, and making demos. I was doing my own punky stuff, not too far away from where they were. Our girlfriends went to the same school.”

I’m guessing you’d been playing guitar for a while.

“Yeah, I was in a band called Strobe Effects, with mates from Forest Hill School, Dacres Road {South-East London}. My mate used to live three or four doors away from the school and we’d rehearse in his converted garage.”

A proper garage band. And as you were born in 1961 and on the doorstep for London, I see you as being right time, right place for punk rock. Were you into prog before getting bitten by that particular bug?

“Not prog. I was always a Sweet, Slade and T-Rex fan, the rockier side of pop, I suppose. And there is there is a little Slade story linked to Haircut One Hundred, because when we recorded Pelican West at the Roundhouse, in the next studio was Girlschool, the heavy metal band. And who was producing them? Jim Lea and Noddy Holder!”

That was Girlschool’s fourth LP, released in 1983, a couple of years after their winning Headgirl collaboration with Motorhead on the St Valentine’s Day Massacre EP.

Meanwhile, it all seemed to come together really quickly with Haircut One Hundred, taking off after recording debut single, ‘Favourite Shirts (Boy Meets Girl)’ at that same Roundhouse studio in Chalk Farm.

“I think the reason Roundhouse was chosen was because it was one of the first digital studios, using the 3M digital {multitrack} recording device. Before that, everything was done on analogue 24-track. The Beat had just done their first album there {I Just Can’t Stop It}, produced by Bob Sargeant. And that’s why we ended up there, because we were using Bob Sargeant, in the early days of when digital was just being trialled.

“There were lots of problems and there was an in-house engineer there to fix the thing, with all these funny little digital blips and hops going on. There was always someone there with a screwdriver. “Hang on, we’ll just have to wait for an hour while what’s-his-face gets his head in amongst the wires.”

And were you soaking this all up? You have your own home studio now, and I imagine Nick and yourself in particular watching very carefully, taking it all in. Did you all have an interest in that process, or were you just about making the music?

“I think some of us took more interest in the engineering side. I definitely did. I didn’t understand what I was looking at, but I kind of picked up the basics, which I’ve carried with me to this day, which I still deal with, recording here at home. And ever since going to the professional studios I’ve always had some kind of recording machine. I’ve always had a four-track machine. And it must have been in the late ‘90s, when recording software became available on computers.”

Have you still got copies of those early demos you made when it was the three of you (Graham, Nick and Les) plus Patrick Hunt on drums?

“Well, I wasn’t using a four-track machine then, not until towards the end of the Haircuts.”

Do any of those early demos appear on this new Pelican West expanded reissue?

“No, but there’s another album if people wanted to hear any of those. But in those days, we went to a normal eight-track studio and you handed over your money, recorded three tracks and went home again. And people recorded over those master tracks. They didn’t always put these things on the shelf, because they’re so expensive. They’d probably sit there a couple of months, then another band would come in and they’d wipe it and record over.”

Did you stay in touch with Patrick?

“I haven’t seen Patrick for a while. He did appear in Cornwall a few years ago, but I don’t know where he is. He went on to work with Sade, I think.”

Was it all a bit of a blur? Because it all seemed to happen so quick, from the first single and album onwards, not least when the teen pop mags took an interest. Did you have time to enjoy it?

“I think with anything in the music industry, you’re either on or off. You’re either a struggling musician, or it’s all full-bore. And once people recognise you’re on the upward trajectory, everything gets chucked at you. Whether you want to do these things or not, a lot of them are part of raising your profile. There’s a lot of things we did which we really loved and a lot of things we did, which we retrospectively look back and think, ‘Oh, no!’”

But you were all so young. You were barely 20 when Pelican West came out.

“Yeah, I remember my 21st birthday, we were off to New York for a gig at the New Music Seminar, I think, right in the middle of Manhattan. Those days, because you’re full of enthusiasm, that’s what drives the band, the enthusiasm for the music.”

I don’t want to muddy any waters, go into any perceived negatives, but for North of a Miracle, Nick was barely 21. I loved that album from the start, and have since gone back to your post-Nick follow-up Haircuts LP, Paint and Paint, and there’s some good stuff on there as well. You were a talented bunch. But part of me wonders if you were listening to Nick’s debut solo LP, thinking, ‘That should have been ours’?

“Unfortunately, when things did fall apart, we already had a body of material ready for a second album, which forms part of this re-release. We’ve got the missing tracks that were unfinished, and some still are unfinished, but it’s impractical – the studio costs for getting it back completely are not really viable.

“Going back and putting stuff on it now would sound a bit weird. And that’s exactly what everyone else thinks. I don’t think Nick would like to sing over a backing track from the ‘80s. But on North of a Miracle there are a couple of tracks which were originally done by the Haircuts, and they’re featured on Pelican West 40.”

Those tracks were Nick’s first solo hit, ‘Whistle Down the Wind’, and ‘Club Boy at Sea’.

“We had Paul Buckmaster in to do the string arrangements. I think some of the parts were replaced by other musicians for Nick’s version. But the original version is on Pelican West 40.”

Those both involve rather sweeping orchestral arrangements on Nick’s debut LP. I kind of assumed that wasn’t the case with the originals.

“We decided there were two tracks we were going to use the orchestra for – those tracks – but it’s an expensive thing to do, to hire a string arranger and an orchestra. You’ll hear these tracks and hear how the band was developing. But we were getting pulled in 50 different directions at once.”

That seems to have been the tipping point for Nick. And I’m guessing it all got a bit too much for everyone.

“Nick would say exactly the same thing, due to those demands for producing a second album, being asked to tour. You know, do you record, do you tour? And being the youngsters we were, we were trying to please everybody, instead of saying, ‘Sod you lot, we’ve got to finish this. Forget about the touring, or do the touring and forget about the album. And in the end, I think if it was too much for Nick.”

When you first heard North of a Miracle, was it a case of, ‘Bastard!’, all a bit raw, or were you ready to face it by then?

“We were kind of under the impression that, you know, there was interference happening, with outside sources. And it’s a really difficult thing to know who’s telling the truth within the industry. It’s a difficult one to answer.”

I guess it was mostly down to the corporate machine and big, bad music industry. You were close friends before and remain so now, right?

“Absolutely. We were always friends. It’s only the industry really, and the things done within the industry are always the downfall of any band.”

Was it a one-album deal with Arista? Only your second record came out via Polydor, I see.

“I think we had a bigger initial deal with Arista. So there was more work that could have been done, but I think we had to change our dealings and record companies after Nick had gone. We had to extract ourselves from Arista just to see what we could do as a second incarnation, if you like. But that wasn’t what we necessarily chose to do. It’s where we ended up.”

Was Marc (Fox) nailed on to be frontman of the reconvened band, post-Nick? Only that was a bit of a surprise that he stepped forward.

“We actually auditioned people, and we had the singer from Secret Affair come along, and interviewed a few other people, putting an ad out. We auditioned a few people around at Phil’s house, but it just wasn’t working. So we thought, why should we bring in someone outside when we could pull someone in-house?”

And there are some lovely moments on that record. It’s just a shame it got lost, really.

“It’s one of those albums … it has got some great moments on it. It’s not a masterpiece by any stretch of the imagination, but it’s what kept us busy until we all decided this is obviously not the master plan really. We’re just kind of making the best of what we’ve got.”

Was there a big gap between that and where you went next? Was it just the fact that it wasn’t a commercial success that made you think to knock it on my head?

“Like I was alluding to, it wasn’t the thing we’d planned to do. Because we weren’t doing it with Nick, it wasn’t like the authentic article, really. While we were in this kind of situation, I think the band members were probably looking at their futures and whether it was fulfilling their artistic needs or not.”

You clearly made some good mates along the way. For instance, you had that link with Glen Matlock.

“That came later, after Boys Wonder.”

I was coming on to those years, that band having released one album, 1989’s Radio Wonder, and five singles between 1987 and 1990. How did that project come to pass?

“We knew Ben and Scott {Addison} from Boys Wonder back in my punk days, before I joined the Haircuts. We crossed paths in those days, going to a few local punk gigs in London. And we actually asked them to come and do some backing vocals in the Haircuts, part two. They came on tour and did some vocals with us. I think at that point we said, ‘Do you want to join us, do something?’ And they said, ‘Actually, we’ve got our own thing, Boys Wonder, maybe you want to come with us. So I did a bit of an audition with them, ending up going that way instead.”

Do you think you deserved a bit more success there?

“Well, they were kind of the complete opposite of what I’d just come out of.”

Which is what you needed, in a way?

“It fitted my guitar style a lot better. I was kind of going back to my roots, regarding musical influences.”

Our mutual friend, Pete, saw you play a charity show in Cornwall told me when he heard you play it was unmistakably you, despite the passage of time. And you do have that very distinctive style.

“Well, I don’t think so. All I’m doing is chucking my own influences in there. My musical influences were Steve Jones of the Pistols, Mick Jones from The Clash …”

Neither related to Graham, despite their respective London roots … far as I know. Sorry, carry on …

“… Stuart Adamson from the Skids, 100,000 other punk bands, Derwood {Bob Andrews} from Generation X was a huge influence on my playing …”

“I alluded to it earlier that you got the chance to see a lot of those bands in their pomp.

“Yeah, I did, because I used to work in the West End, in ‘77. I was a little too young and just missed on seeing the Pistols, but that’s when I picked up the punk thing at school, but around ‘77 I was buying and going to see The Clash all over the place, Generation X, the original {Adam and the} Ants, the Ramones, The Rezillos …”

Fantastic days, so to speak. The latter two alone, I love their live LPs, really felt like I was there. And you probably were.

“I was at the New Year’s Eve concert …

“At The Rainbow?

“Ramones, Generation X and The Rezillos, I think, were on the bill.”

Marvellous.

“Yeah, I’ve been to some great gigs and picked up some amazing influences, which is what I put into Boys Wonder and the Haircuts as well – it’s a completely different thing that I bring to Haircut One Hundred. I kind of bring … I don’t know, you’d have to tell me what I bring to them!”

I was going to say – same as I put to Nick a few years ago – you never had the kudos of the Postcard bands, for example. A lot of contemporaries were seen as a lot cooler. But maybe it was the fact that the teen mags and young kids latched on to you more, screaming at Nick and so on. Yet there were so many great influences at play there, and what you were doing wasn’t so far off what Edwyn Collins was doing with Orange Juice, alongside Zeke Manyika and co., a real mix of influences involved. And it worked so well.

“Well, you hit the nail on the head there. We were a lot edgier when we started out and we were cooler in many respects than we might have been perceived to be later. A lot of our early influences were Orange Juice’s, and we had a connection later on, Nick’s girlfriend and my girlfriend both from Glasgow, and they used to love us up in Scotland, along with Aztec Camera and Orange Juice.”

I believe you got to know Jimmy Pursey and Edward Tudor-Pole from your working days in London’s West End too.

“I think that’s when Nick and Les came to see me play. I used to work in a photo lab and one of my friends who worked with me, Phil Payne, was in a band called The Low Numbers, kind of a post-punk /early Mod kind of band. His drummer was a really keen football fan, and I could play drums – I learned drums at school – so whenever their drummer disappeared off to see Arsenal, it was, ‘Derek’s gone off to the football, can you come up and drum for us?’ So I’d jump on the train and go up to the youth club in Great Portland Street.

“Around that time, I was also learning to play guitar and played with The Low Numbers with Jimmy Pursey and Chris Foreman from Madness. And Eddie Tenpole as well. We did a fundraiser for that youth club, where we were rehearsing, a place for the kids on the local estate to hang out. I think it was a Christian club. The bloke who ran it was a really good bloke, always out for the youngsters, this youth club he used to run so passionately in this basement.”

Returning to Boys Wonder, how long did that continue? I see you moved down to Cornwall in 1990. Was it still happening around then?

“With Boys Wonder, it was a real comet. You always hear that analogy about things burning fast and bright, and we were on a really high and fast trajectory, with a following on the fashion scene, our girlfriends and friends all connected with fashion or music, the girls making our clothes for us – Ben drawing the designs and the girls making them, adding their influences. Then we had our musical influences, which was a lot of the punk stuff, a lot of T Rex, while Ben and Scott were interested in jazz, and musicals – there was a lot of Oliver in there – and Anthony Newley, all this stuff being rolled up in Boys Wonder, the creative process.

“The press didn’t get it, there was a very strong underground movement, but we couldn’t get out of that and convince anyone the songwriting was far more superior than what they were perceiving at the time. We were signed by Sire in America, but weren’t really backed to any extent that would enable us to spend more time and more money on it.”

Were you working by day again at that point?

That wasn’t the case with the Haircuts.

“We were all working, trying to get by.”

“No, we were all professional musicians. With Boys Wonder it was completely different, almost going back to square one again, proving ourselves as a band, which we kind of did to some extent. But we ended up as a bit of a cult band as opposed to other bands alongside us, good friends at the time like {Doctor and} the Medics, who got to No.1. But good for them.”

There were so many great bands from that era who missed out on the big time, but were later cited by those who broke through with Brit Pop and so on as big influences. In that case, perhaps the right place but the wrong time.

“Yeah. And we were most definitely pioneers, and we do get quoted by other bands. But that’s the luck of the draw in the music industry. You do your damnedest and then nothing happens.”

As long as you’re having fun doing it though, and have stories to tell your kids about, that’s great, surely.

“Yeah.”

And you did get to play in Glen Matlock’s band and support Iggy Pop in Europe in your next venture.

“Yeah. Well, at the time there was another band called Lightning Strike, and Crazy Pink Revolvers, with Theatre of Hate, CSM 101 … There was a group of bands doing various things at the time. And the singer of Lightning Strike, Dave Earl, writing something for his girlfriend, who wanted to be a singer, and they asked me and another Boys Wonder member to do a bit of backing to record something to see if we could get her a deal. We did that and asked Glenn to play bass on it. I said, ‘You can’t ask Glen!’ But this manager of ours said, ‘If you don’t ask …’ So I asked, and he said yeah.

“He did it, and liked what I was doing, so asked me to join his band. I think at that point Boys Wonder had gone as far as it could go. We kind of hit that rock brick wall again, nobody taking us seriously, kind of going round in circles. So I joined Glenn’s band for a short while and did this tour around Europe, which was good fun. And I was in the band with Steve New {later Stella Nova}, also from the Rick Kids, Glen on bass, Dave on drums, me on guitar, and Justin Halliwell, currently playing with Glen again. We supported Iggy for a bit, but I think at that point Steve was going downhill with his addictions, and I liked being in the band but didn’t really want to go round the whole thing again.”

And you were already heading down to Cornwall a lot in your spare time by then, right?

“I was, I was visiting here since the mid-‘80s, a seasoned traveller to Cornwall and already going surfing, coming back to visit friends here for Christmas and Easter. My life has already taken a turn.”

The heart was clearly pulling you towards Porthtowan.

“Yeah, I think I said to Glen in 1990, ‘Once I’ve done this tour, I’m going to move to Cornwall,’ which I did, and then I kind of stopped music as a profession, just to do something different for a bit.”

You always kept your hand in though, from teaching guitar and everything else, setting up the studio and all that.

“And there’s nothing to prove anymore, is there. It doesn’t really matter. Music should be a creative process and shouldn’t be there for any other reason. It’s an art, and it’s the reason why we started in the punk days, in the early Haircuts days, because we were all enthused and all creating something. We didn’t want a record deal at that time. I mean, everybody dreams about being on Top of the Pops, but you don’t do it for that reason.”

With quite a few of the musicians I speak to, the ambition was just to get a John Peel radio session or make one single, even those who ended up doing far more.

“Well, nobody plans for anything bigger than that, because it doesn’t happen to most people.”

You clearly have that parallel love for Cornwall, something we share, you’re a keen supporter and fundraiser for Surfers Against Sewage {SAS}, and aways had that love of surfing and surf music. It was all meant to be, it seems.

“Yeah, Jan and Dean, Hot Rod music, ‘50s rockabilly, it goes partly hand in hand with the surf culture … not really in the middle of winter though!”

Are you out and about on a board still?

“No, I go in bodyboarding in the summer sometimes, but I decided I was a better guitarist than a surfer, so I let the surfers carry on and get the waves while I’ll go in and enjoy myself if I feel like it. I’ve had some great times surfing, but most of my surfing took place in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s.”

“And as you know, the SAS is still going, and I helped set up first surfers’ ball down here.”

It’s a proper community where he is too, and the day we spoke Graham was getting ready for that evening’s Porthtowan Surf Lifesaving Club Christmas Awards at the village hall, along with his wife, Bertha, the pair having met not long after he moved to Cornwall, recently organising a fundraising campaign for a rescue long board made by former British longboard and shortboard surf champion turned ‘shaper’, Ben Skinner, in memory of local former lifeguard and keen surfer, Neil Walters.

“There’s a real connection there, with the surf club, and our daughter’s a lifeguard as well.”

Graham has two sons too, the older lad also a guitarist, working for the RouteNote music company in Truro, the other based in Wales. And while a Londoner through and through, Graham was born in Bridlington on the East Yorkshire coast, his Dad serving in the RAF at the time. But perhaps the call of the sea was always there.

“Maybe.”

And are you looking forward to or secretly dreading that Shepherd’s Bush Empire date with Haircut One Hundred?

“Not dreading it at all. It’s going to bring a lot of people together, a lot of friends who haven’t seen us for a while, and a lot of people looking forward to the release of the unheard material. And we were quite surprised it sold out so quickly.”

Is there a likelihood of a second night being added?

“Erm, I can’t really say. I expect something will follow on from it, and because things sold so quickly, that’s going to prick up the years of other promoters.”

Well, maybe the surfers’ ball next year will feature the Haircuts down at Porthtowan.

“You never know.”

Any details on who’s going to feature in that Shepherd’s Bush show?

“No, we’ll keep it to ourselves.”

Fair enough. At that point, Graham reminded me of his involvement with another band in more recent times, The Continental Lovers.

“I met the singer when he was on holiday in Porthtowan, we got chatting and I ended up being invited to play on a few tracks just to see how it would go. Joe, the singer, was really pleased with it and I really enjoyed playing on it, because it was kind of down the Boys Wonder route as opposed to down the Haircuts route.

“They’re based in Gloucester, so it’s not really practical for me to get involved, and they’ve got another guitarist playing my parts now, more their age group, someone who fits in and has got all the tattoos and everything! But playing the music came quite naturally, and they’re definitely a bunch worth looking out for.”

And if you could just pick a highlight of your days with the Haircuts, in the studio or on stage …

“I think for all of us, probably, going to the States was a massive bonus. For me personally, it definitely was.”

Do you still pick up the phone and talk to each other now and again?

“Yeah, we do.”

And is that easy conversation, old blokes being nostalgic?

“There’s always nostalgia, and you go over old ground and remind each other of the stupid things you did and who we met. That’s all part of it. But we kind of look to the future with a positive and a new vision. There’s no guarantees there for anything.”

That’s one thing with the pandemic and so on. That taught us a few things about the fact that you can’t take anything for granted. I wonder if that formed part of your resolve for getting this together – the whole reunion, reissue and live project.

“Yeah, the reissue was bound to happen because of the 40-year anniversary. But the company that decided to take it on have really done a good job, they’ve been really supportive, and they wanted the band to be completely included. They haven’t done anything that we’ve disagreed with. They haven’t just bulldozed in, licenced the tracks and released any old crap. They’ve really tried to include the band, and the Shepherd’s Bush Empire show is part of promotion for that release.”

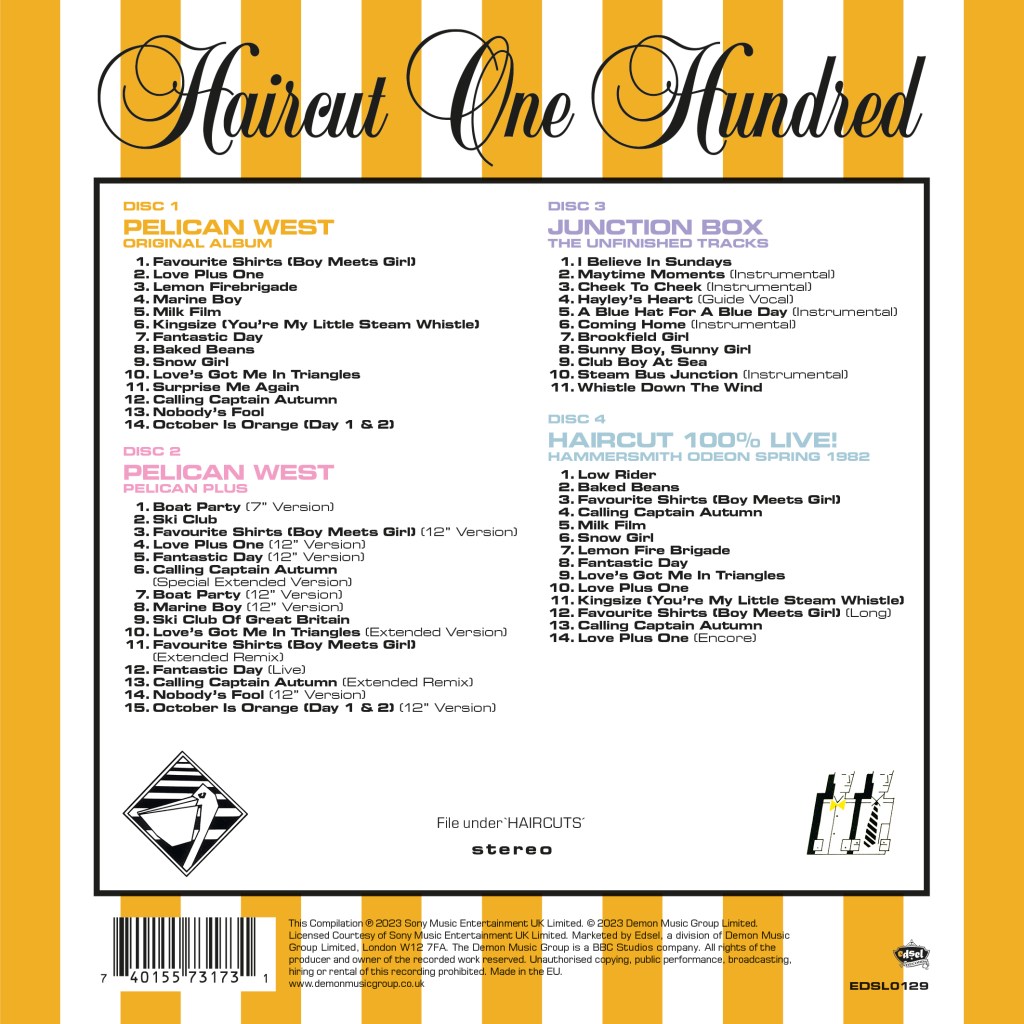

The super-deluxe edition of Haircut One Hundred’s debut LP Pelican West – originally released in February 1982 and spending three months in the UK top-10 album chart, 10 weeks of which were it was in the top five – includes non-album single ‘Nobody’s Fool’, added to the CD and 4-LP set, the new version of the LP featuring a remaster of Pelican West, all the 12” mixes and B-sides, a live set from Hammersmith Odeon, and for the first time, demos for their unfinished second album, given the provisional title, Blue Hat For A Blue Day.

Over four CDs, there are 54 tracks, of which 24 are unreleased, including nascent versions of later Nick Heyward solo hits ‘Whistle Down The Wind’, ‘Blue Hat For A Blue Day’, and the ‘lost single’ ‘Sunny Boy, Sunny Girl’.

The 4-CD set features a 44-page booklet with 10,000-word sleevenotes featuring an oral history of the time with all six members, interviewed by the set’s curator, author and DJ Daryl Easlea. The booklet also includes memorabilia and exclusive photographs from the personal collection of Haircuts guitarist Graham Jones and bassist Les Nemes. Pelican West 40 is also available as a half-speed master vinyl LP as well as a 38-track 4-LP edition containing the new half-speed cut of the album along with the unreleased second album tracks and a collection of 12” mixes. For a track listing and details of how to pre-order, with the new package set to be released on February 24th, head here.