Mick Talbot was at home when I called, ‘learning stuff, swotting up on homework.’ And four decades after truly making his name with Paul Weller in The Style Council, he tells me he still has ‘various things going on, no two days alike.’

Homework in this case involved learning a set for revered soul band Stone Foundation, having played on their most recent albums, covering for keyboard player Ian Arnold at two shows where the Midlands outfit supported Madness at The Piece Hall in Halifax (last weekend).

“I know quite a lot of this stuff, and a lot they’re putting in the set I played on anyway, having known them for a little and having jumped up at a few of their gigs, playing the odd one or two things… but I’ve not done a full set with them. That’ll probably be quite a laugh, and helpfully they’ve chosen a set-list which incorporates a lot of songs I played on anyway.”

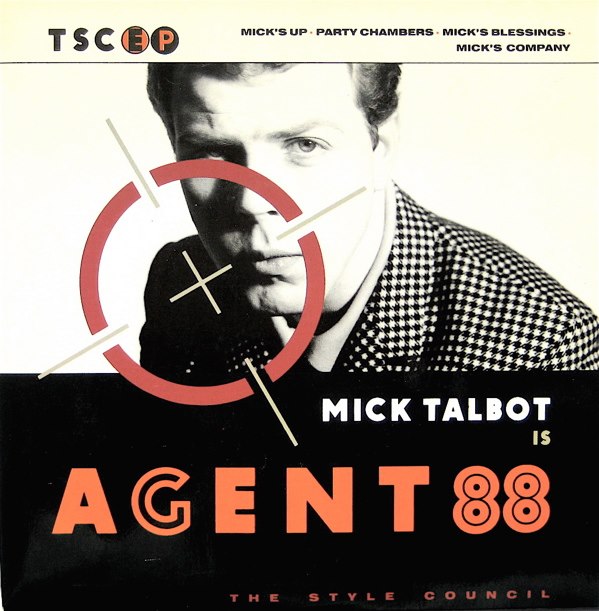

As well as his key role, so to speak, in The Style Council, the band Paul created after breaking up The Jam in late 1982, Mick has also featured over two stints as a member of Dexys Midnight Runners and also with their off-shoot The Bureau, having initially earned his introduction to the music industry with Beggars Banquet-signed Mod revivalist four-piece The Merton Parkas, their name alluding to their South London suburban manor.

And it seems that Mick, 64, remains busy, his CV of live and studio work down the years also including engagements with Candi Staton, Galliano, Jools Holland, Wilko Johnson, Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend. And then there are the collaborations with former-TSC bandmate Steve White and Ocean colour Scene’s Damon Minchella, while also featuring on various Weller LPs.

We started out by chatting about my last sighting of Stone Foundation, with The Jam co-founder Steve Brookes supporting at the Boileroom in Guildford, a cracking venue but one where this eight-piece band struggled to all fit on the small stage, understandably ruling out the chance to head back up a tight spiral suitcase to return to the dressing room before any encore.

“Well, that can be a bit of a pantomime. The Jazz Café at Camden was a bit like that. They’ve converted it now, so the dressing rooms are on the same level as the stage, but that used to be such a palaver. If the act did want to go off, they had to go up, through the restaurant and the balcony, all the way around the back.

“Those places are intimate, but you know, people are so aware of you and at times you can feel like, ‘Hang on, this is a charade. Are these the rules we have to play by, these ornate showbiz rules?’

I know. It’s perhaps the antithesis of the Spinal Tap search for the stage, lost in a huge venue, trying to find the way out.

“I suppose so. Even writing a setlist, it’s a bit presumptuous, when you see them assume, ‘Right, first encore, two numbers…’ Maybe wait to see if they like us, first!

It is all a bit music hall, isn’t it.

“Well yeah, you could be running off, rotten tomatoes thrown at you, only getting two numbers out, let alone two in the encore!”

In contrast, I think of the late ‘90s idea of front-loading albums so you have all the potential hits at the start, rather negatively assuming your market won’t have the staying power or commitment to listen to a whole album. That’s not how we fell in love with music, was it?

“No, but a lot of that’s changed drastically.”

As we mentioned Stone Foundation, Lee Cogswell made a film with them recently, as was the case with you and Paul for rather splendid 2020 documentary film, Long Hot Summers – The Story of The Style Council, which certainly inspired me to dip back into all those records once again. And although Cafe Bleu and Our Favourite Shop have never been far from my record player, the cassette player in my car, or the CD player since, there were others I went back to for the first time in a long while, including The Cost of Loving, which took me right back to early ’87, aged 19, the world ahead of me.

As it was, I think I probably tried too hard to like it at the time, struggled a little, then got into it, but life was changing so much, and I soon moved on to the next thing. But it was lovely to go back, hear it afresh, appreciate it for what it was. And I don’t need to tell you this, but music has that power to transport you back to a time and a place.

“Yeah, well, that documentary has done a lot of good like that, reminding people who were around about certain bits that they might have overlooked or people that might not have even considered us at the time. Also, in recent times I’ve been at a few family do’s and been quite surprised at people under 30 and their knowledge of it, and that’s only come about in the last couple of years. And that documentary opened it up to a lot of people.

“And that’s the thing now, I suppose with the internet, so much is available to people that if you want to pursue something from the past, it’s a lot easier. It’s not such hard work. I remember as a kid liking records that were made before I was born, taking them as an influence, but it was a bit of a quest sometimes, to find things.”

That does add to it, mind, making the effort worthwhile. In those days you felt like you were part of a select band who had taken the trouble to find a certain record or book or film.

“Oh yeah! With the internet it seems that everyone knows everything about everything. But do they necessarily care about it? Sometimes, if you had a passion for a certain thing and it was a little leftfield or niche, it was true passion and you had to work at it. But now I guess people that click the mouse can have intimate knowledge of something which they’re not that bothered about!”

Whereas in our case that knowledge would be the key to forging friendships with like-minded souls that might last a lifetime.

“Yeah, and I suppose you sort of develop tribes. But I don’t want to sound like a dinosaur. I think it might have made people more broad-minded and accepting of things that they don’t think is their thing. And I don’t think youth culture is quite so tribal and compartmentalised. You don’t think, ‘He’s a goth,’ or ‘He’s a heavy metal geezer,’ or, ‘He’s a rude boy.’ I don’t think it’s quite like that anymore. My son’s not embarrassed about liking certain records that I think I couldn’t even admit to liking back then! And he’s got quite good taste. He’ll say, ‘What’s your hang-up? It’s just music.’ But as a musician, you’re probably the snobbiest of all about those things.”

At that point, carrying on that line, I asked Mick what he made about Slade in his formative years, by way of an example of past tribalism and the like (the result of which you’ll find in Wild! Wild! Wild! A People’s History of Slade, set for publication in late summer), and that got us on to bands he saw in his formative years (having caught Slade at Hammersmith Odeon, most likely mid-May 1974, when he was 15). Did he see a lot of acts around then?

“Well, I’d tag along with friends, get tickets, and see a lot of people at Hammersmith Odeon and loved going up to The Roundhouse at Camden on a Sunday. They used to have about five bands on, and they’d all be from different tribes. I remember seeing a line-up where the top of the bill was The Kursaal Flyers, who I suppose were sort of pub rock, somewhere in the middle was Crazy Cavan and the Rhythm Rockers, who were Welsh rockabillies, and the bottom of the bill was a five-piece band called The Clash. That was about six months before they made a record, with Keith Levene from Public Image in there. It was really odd. I mean, they certainly had a presence, but I couldn’t really say much about the music – their amp blew up on the second number! Then Joe Strummer started having a go at someone in the crowd, and they were off, and I thought, ‘Well, that was a bit mad!’

Were you aware of The Clash before that show?

“Not really. They were just on the bill. And in that way, I saw a lot of bands that I wouldn’t have gone out of my way to see. I’d see people like Gong, just some mad sort of… they had flying teapots as part of their act. All sorts of mad hippie bands, like Hawkwind and Pink Fairies. At the same time, I might be going there because Graham Parker was on the bill. They used to mix it up such a lot there.

“You were getting the beginnings or leading up to what was going to be called punk. But you still had the sort of tail end of, I suppose, the late ‘60s and the whole hippie movement at The Roundhouse.”

As you mentioned The Clash, I recall the young Mick Jones was there a lot in that previous era, taking all those bands in. And it’s interesting that you mention Graham Parker. That’s someone who for me doesn’t get the kudos he deserves. He was always there or thereabouts.

“Yeah, I guess people lumped him in with Costello, but Elvis was a bit more variety in the way he put things across. I also think Elvis was ambitious, and I’ve got to know Graham a little bit – I worked with him in the early ‘90s and I’ve bumped into him a few times when he’s been collaborating with Stone Foundation. He’s very much his own man. I remember that documentary with Dave Robinson {Stiff Records co-founder} saying a lot of people ask him to compare them, and he said Elvis Costello had no problem about taking on that name as it would get him attention, but if he’d have told Graham Parker to change his name – a lot of people said his name was too similar to Gram Parsons and maybe he should do something about it – he’d have just told him me to sod off, like it or lump it. And that’s the difference between them.”

I always felt that GP, like Van Morrison, embraced and took a new slant on soul music that made you look at all that in a different way.

“Oh, that first album, definitely. Even to the title {of early single} ‘Soul Shoes’. That’s why he really worked for me and a few of my friends when he came through. I didn’t know so much about Van Morrison, but I liked bits and pieces of Dylan, and Springsteen was starting to make inroads, but then he came along, certain tracks having an influence from people like Solomon Burke, but it seemed very current as well – he had that energy coming out of pub rock, I suppose. Pre-punk.

“But like a lot of acts then, he got a bit of attention in America, went out there for a long time, and when he came back, punk had exploded, and it was almost like it was decreed he might have become yesterday’s man overnight.”

That’s true, and I guess that may explain why he was often on the fringes, more underground.

“Yeah, but people that care about him do care about him. I know that Joe Jackson, when he broke, a lot of people said, ‘Oh, you’re a bit like Costello,’ and he said, ‘I’ve got more time for Graham Parker.’ I remember him saying that in an interview at the time.”

I’ve only got to see him once, at the Town and Country Club (now The Venue) in Kentish Town, touring The Mona Lisa’s Sister, a great record, in early November ’88.

“I played on the album {not long} after that, Burning Questions.”

Did you stay in touch?

“I hadn’t seen him for a very long time, but then the Stone Foundation made a connection, because he often supports them when they’re in London. In fact, the last time I saw Stone Foundation at Koko – the old Camden Palace or Music Machine – I’d found something in my loft when I was clearing out, the string quartet score to one of the songs, ‘Long Stem Rose’, took a picture of it on my phone, and thought if I bumped into Graham backstage, I’d show him, all the way back from ‘92.

“When I showed him, he went, ‘Oh, my God!’ That was a weird one. He had a string quartet arrangement done by somebody in New York, it was faxed over, and he didn’t have anyone in the studio with him that could read music. He asked if I could. I said, ‘I did once, a very long time ago, but not much.’ He went, ‘If I give you this overnight, can you have a look, because I’m not gonna know. See how far you get.’ I could kind of work out what it was supposed to be. He was more impressed than he should have been. I said, ‘Don’t send me out with a baton though!’

Going right back to your music roots, did you have piano lessons at school? Was anyone else in the family already playing music?

“We lived with my Nan and she played the piano. It was always essential to her. I remember, when we moved, she was a bit upset we couldn’t take the piano with us. We’d only been in this new place for a matter of days and a piano arrived, hired. She just felt every house should have one – more essential than hot water or central heating! I guess in her childhood that may have been, pre-telly and radio, the most compelling form of entertainment in the room.

“She’d play by ear and I asked her to show me some things. She tried to, but said that because that was just from instinct, ‘I don’t know how much more I can show you.’ So she got me piano lessons. I didn’t really like the idea of that. I just went ‘no, I like it when it’s just magic.’

“I could play a little bit by ear, but I did go to lessons for two or three years. It always felt like an interference to me. I was more focused on playing football than going to lessons, but most of it went in… so I’m a bit of a mixture, really.”

Was that Merton Park or somewhere around there?

“Yeah, we were in Tooting when we left the old piano behind, about three stops up the Northern Line.”

Was there plenty of music on the radio at home?

“Yeah, my mum listened to the pirate stations in the ‘60s, because they were playing the most soul, I suppose. She liked Tamla and all that.”

You clearly came from a cultured background, music-wise.

“Well, she liked all the bands around then. I seem to remember her liking The Searchers quite a bit, things like that. And my dad was always into modern jazz, a sort of music I didn’t really understand until I got older and could then make some sort of connection… when funk started embracing it, as an offshoot of soul. My dad would hear me listening to funk records and say, ‘That’s a bit like modern jazz,’ and you’d think, yeah, there is a thin line on some of it. Then he played me a few things he thought I’d like. I sort of understood it more and saw that it was all the same thing really.

“I was trying to adapt. I wanted to play piano to music I wanted to play, and I think a key moment was getting a K-Tel rock ‘n’ roll compilation. I was aware of The Beatles, but this was, ‘Hang on, this has got lots of people they’re always talking about on it, like Little Richard, the Everly Brothers, Chuck Berry…’ Their roots, so you’re focusing on it because of them. And my dad said, ‘You know that rock ‘n’ roll is just blues? And 12 bar blues is just three chords, so once you know the key…’ I was like, ‘Blimey, why didn’t someone tell me this ages ago? This is the key to the universe!’ I started jamming along to all those things, that opened up a lot of things.”

Was it always piano, or were you picking up a guitar?

“My dad had a guitar and my brother played it a bit. I can play guitar, but never owned one. I know where the chords are, but wouldn’t say I could play it very well. I don’t know why, but I like the piano – it’s just that thing, thinking my nan had that magic! I think the fact that she said, ‘I don’t know, it just comes into my head,’ intrigued me even more. I never quite got over that. That stuck with me.”

What’s the age difference between yourself and younger brother, Danny, the Merton Parkas singer and guitarist?

“He’s two and a half years younger.”

The Merton Parkas, for those not up to speed on that era, had one minor hit with ‘You Need Wheels’, making a few singles and one LP, Face in the Crowd. Was that more of a family thing at first, I asked Mick, or was it always the four of you?

“I was in a band with some others, the guitarist left, Danny had started singing with a band, and we were just doing working men’s clubs, mainly around Colliers Wood, but not exclusively there. It seemed to be about four or five clubs around there, one Fry’s Metals Foundry Club by the river Wandle. We had a regular gig there and at constitutional clubs and British Legions. We’d go all over London and suburbia, playing them sort of places.

“It was a varied line-up, but usually the same drummer and bass player. Danny started singing with us a bit, then the guitarist left, and Danny could play guitar and we decided to see if he could fill in for a couple of gigs, bluff his way through. And he seemed alright at it, so he carried on.”

As for Mick’s own family, he has a son, telling me, ‘He’s a big man now, 37!’ Has he followed him down this career path?

“He likes music, but I guess he’s seen the ups and downs of it. It can look like you’re always busy and omnipresent, but it’s not always like that. But he appreciates it. I showed him a few things, and at one point he fancied being a drummer, but then realised that was a bit more difficult than people might think. I sometimes think kids think drums was the easy one. It’s not at all!

“Then he started playing harmonica, and he quite liked that. I was happy to encourage him and show him things, but wouldn’t want to force him to do things, because I wasn’t forced to. It was something I was drawn to, much as I didn’t like my piano lessons. I did like being able to play the piano though.”

On the subject of The Merton Parkas, did that deal with high-profile indie label Beggars Banquet come about fairly quickly?

“I think we’d been going a fairly long time, under a few different names. Then we broke away from playing working men’s clubs, where you’re pretty much expected to play things people know. Which is fine for a while, but if you want to try and develop something… we used to look forward to playing in pubs. They paid about half as well as working men’s clubs, but didn’t mind you playing your own material. We tried to sort of cross over to that, and that led us to get in places where we’d be seen more. Then we got in with an agent before we got a deal, who might put us on as a support at The Marquee, and then you’re touching people that have more influence or may want to take you on. We were fortunate that we had a residency in a pub in Clapham…”

Was that the venue where you were ‘discovered’ by music journalist Alan Anger?

“Yeah, there was a couple of guys that were friends with The Jam. One of them, Walt Davidson, did photography and shot some of the live shots on the first single. And his mate, Alan Anger, wrote for Zigzag magazine and had a fanzine. They’d both come down and see us. They were friends with a few bands. They knew The Lurkers, and they were on Beggars Banquet. So I think Alan and Walt probably mentioned us to The Lurkers or someone at Beggars Banquet, making that connection.”

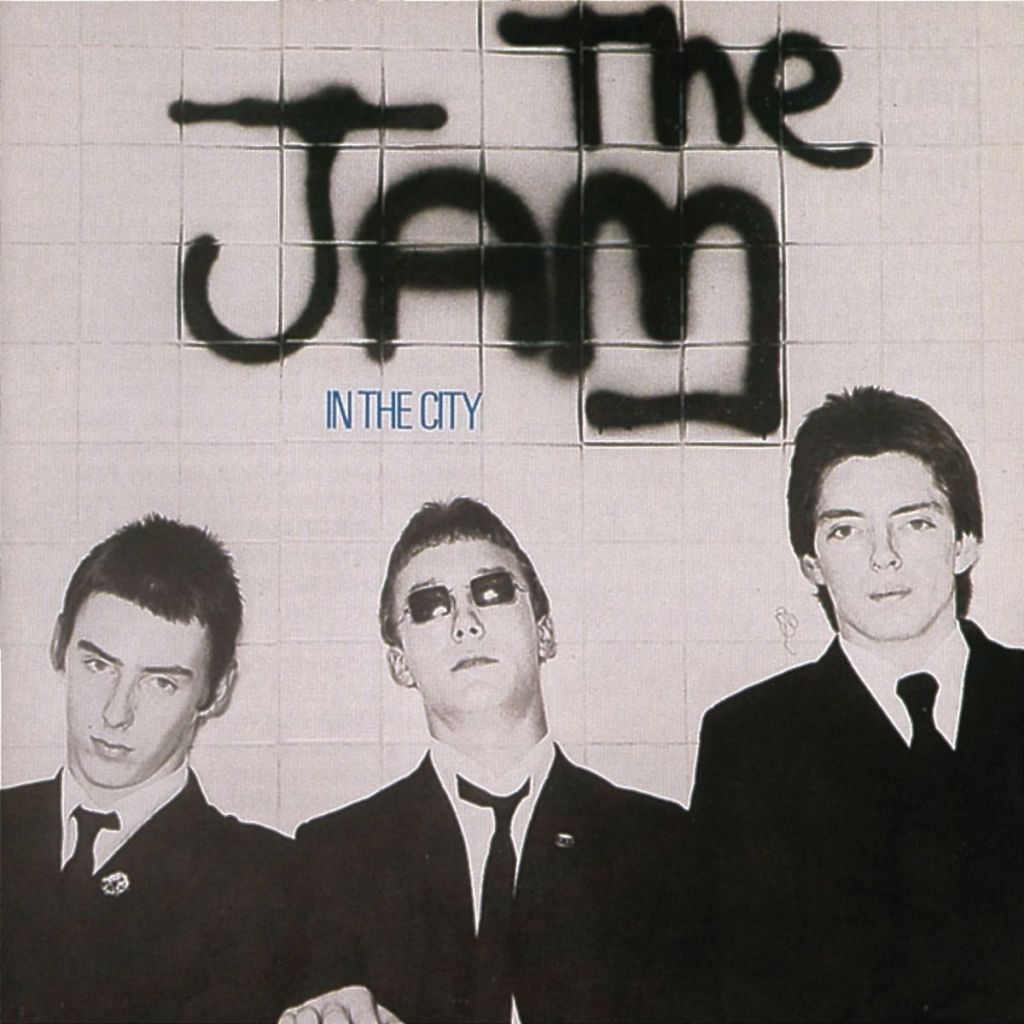

Were The Jam on your radar back then?

“Oh yeah, I saw them before the first single came out, very early ‘77. They did a month’s residency at a pub in Hammersmith, The Red Cow. My friend Clive went the first week and we went to the second and went there twice or three times. That second week, there was a queue around the block. I think they’d already been signed, but nothing had come out. They had badges, one with ‘In the City’ on it. And we just knew that was a song in the set, but I don’t think that come out until later.”

Didn’t Paul’s initial badge say, ‘In the city there’s a thousand things I want to say to you’?

“It might have. Ha! I think they played that twice in the set. They didn’t have very many of their own tunes in there. What was good about it was that they played a lot of songs I knew, some of which I played in our bands. And as much as it was that nihilistic sort of punk sound, they were still playing ‘In the Midnight Hour’ and ‘Sweet Soul Music’, or whatever, in a way that I imagined The Who would, that sort of power trio way.”

I’m guessing ‘Slow Down’ was in there too.

“I think that was in the set, and one track from the first Who album. Not a single. ‘Much Too Much’. I had the first two albums, and I knew that and just thought, ‘I wonder how many other people know this.’ They could have played ‘My Generation’ or ‘Substitute’, but that was quite subtle really.”

Did you get to talk to them?

“No, I didn’t meet them until a lot later – in ’79. Paul rang me up and said he’d heard the B-side of our single, a piano thing, and said, ‘I want something in that style.’ He wasn’t too specific, he just went, ‘I like what you did on that, can you do something like that on this? It’s gonna be the last track on the album. Do you know ‘Heatwave’? ‘What, the Martha Reeves one?’ ‘That’s it, yeah.’”

Did you feel you were stalling somewhat with The Merton Parkas at the time?

“Not at the time, not when I did that. It was the summer of 1980 that I think we ceased to be. We got signed in May ’79, had a year of it and then got dropped by our label. And it transpired that it would be difficult to get signed again. You’d run your course and that was that. Most of the band still wanted to do things in music, but I think we realised that to carry it on it was already a bit tainted.

“I think my brother was offered a few things that he was thinking about, then I got sounded out by Dexys and ended up joining them. It’s not like I got fed up with it. The world got fed up with us! One door shuts, another opens. It wasn’t a calculated thing, and it was very fortunate.

“Dexy’s supported us a year before and a few of the guys remembered me at the soundcheck. We had a talk about music and a chat about Geno Washington, and they didn’t even have the song ‘Geno’ then. But something about the arrangements of two of their songs and the way they put them together, I said, ‘That’s really like that live album by Geno Washington,’ and Kevin went, ‘Yeah, well, JB used to be in his band. So maybe that’s where we got that sort of vibe from.’

“And {later} they just remembered me, and Kevin said, ‘Your name came up. Our keyboard player’s left {Pete Saunders} and we haven’t got very long – I think it was five or six days – until we go out to Europe on tour. Come down and have a play with us, we’ll see how it goes.’

“Then they just went, ‘Yeah, I think that’s alright. Do you reckon you can learn the set and come back in five days and go to Sweden?’ or wherever we were starting. So it was a bit of a mad week!”

And what an album to learn, Searching for the Young Soul Rebels. A classic. In and around my all-time top-10 since I first heard it as a young teenager.

“Yeah, it was a shame not to play on it, but it was nice to reflect that in a live set. That’s my favourite album by them, and I think that’s the result of a team. Having got to know all of them and the background to it all, I don’t know if the credits always reflect what a team effort that was.”

It certainly wasn’t just the Kevin Rowland Band.

“No, but I do think after that, it sort of did become so. But that band had been together three years, working really hard towards that. It was a result of so many different things. Even the youngest, Stoker on drums and Pete {Williams} on bass, contributed quite a lot. Pete was quite… I think in retrospect, he was quite naive, only about 18, but he contributed quite a lot to ‘Geno’, having lots of strong ideas about the arrangements. I just thought it was a really good album, and it was really refreshing that it was so influenced by American soul but at the same time it didn’t seem like one of these sort of Blues Brothers bands or the Q-Tips or any of them. And it had its own thing, lyrically.”

It’s clearly stood the test of time. It still sounds so fresh when you put it on. But was it a case of bad timing on your part that the Dexys you joined was kind of over before you knew it?

“Well, yeah, I think there were cracks there when I turned up. I don’t know if it was a power struggle or whatever. It’s hard keeping a band together when there’s only four of you, but there’s eight of them. That’s a tall order.”

You did some stuff in the studio with them that first time though.

“I did. We did ‘One Way Love’ and ‘Keep It’… although there were three or four of them! And a few others which may have seen the light of day on boxsets since. I might have ended up on the B-side of the official release of ‘Keep It’. Kevin kept re-recording that, I don’t know what happened. Yeah, it was a funny time to come into it. But out of that…”

… came The Bureau.

“Yeah, which didn’t last that long, but that was a hard band to put across really. We were endlessly criticised in the press for sounding too much like Dexys. But… that’s a bit like telling people to not sound like themselves!”

As for The Merton Parkas, Danny Talbot moved on to work in the travel business. As for Mick, after The Bureau came that fateful reunion with Paul Weller. Had they become mates socially? Or was it a bit of a surprise when he mentioned a new project once The Jam were done and dusted?

“After I did ‘Heatwave’, I played live with them at The Rainbow when that album {Setting Sons} came out, but I didn’t see them for around six months, and then he said, ‘We’re going to hire a Hammond organ and want to do three or four soul tunes near the end of the set, and can you do a couple of other tunes that have got organ on them?’ I played about half a dozen songs with them for a couple of nights, again at The Rainbow, probably 1980, just for the London dates, then didn’t hear from Paul for probably 18 months…

“Until the summer of ’82 when he got in touch and said, ‘Look, you’ve got to keep this under your hat but I’m wrapping up The Jam and I’ve got a few ideas, are you interested?’ At that time, it seemed full of potential but I wasn’t quite sure how lasting or what it exactly would be, but it sounded like a good prospect.”

What strikes me now, in retrospect, is the fact that, for me, maybe The Style Council were arguably far closer to the meaning of the term Mod than either The Jam or The Merton Parkas – regarding that spirit of adventure, a leftfield move away from the numbers, so to speak.

“Possibly, I think it was important for Paul to know you had some background in it. We were quite surprised at how many books we had in common and things outside music that influenced us growing up, so that helped us well – you didn’t have to sort of explain things to each other. And I was already aware of Colin MacInnes. My dad had some of those books from that trilogy. Paul surprised me with his depth of knowledge about stuff. It was almost like we were playing a game of chess, taking an examination on Nell Dunn, Ken Loach, French New Wave…”

I get the impression it was something of a release for him, away from the pressure, at least for a while. But how about you? Did you feel under pressure in such company? He’d been there, done it, and he’s always been a grafter.

“Kind of, but he was the one taking the risk, really. I sort of had nothing to lose, and had to reflect on the past three years. I’d done a normal job until I was 20, ended up in a band that got signed, that lasted a year, then joined another band that folded in about four months, got dropped by their original label, then I was in another band that lasted a year, and got dropped by their label. So there I was at 23, and maybe I needed to go back to the real world. Maybe this escape with the circus was coming to a conclusion… and then Paul rang me.

“The funny thing is, in the same week Paul rang me up, Kevin Rowland’s manager rang me to try and get me back on board. But the thing is, Paul rang me personally, while Kevin got his manager to ring me, and that might have influenced the way I felt about it. I did meet his manager, but he said Kevin was a bit anxious about meeting me – he thought he might have let me down with the thing that happened a few years before… even though I wasn’t part of the original band and I didn’t hold any grudge. But I just thought, you know what, when I met Paul, he’s about four months older than me, all our reference points were very similar, and his background and family seemed to have lots of parallels with mine. I had more in common with him, even outside of music.”

It was very much a family. I get the impression you joined the family when you joined Paul – John, Ann, Nicky…

“Oh, yeah, and that was quite refreshing as well, because even though I’d only had three years proper in the business – it’s a cliché but it’s true – it was quite refreshing that Paul’s set-up seemed like a family business. You might not have known it was in the music business. John could have been running a building company or greengrocer’s or something. It just felt like a family business, and there was none of that sort of superficial facade. It might sound corny, but it just felt more honest and what you saw was what you’d get. And there’s a lot of posers in the world of music, and quite a lot of people that just wing it, with more confidence that ability.”

In time of course, he would return to the Dexys fold, on board again from 2003 to 2013, including key contributions to comeback album, One Day I’m Going to Soar, a truly worthy successor to those three first albums. But that’s a story for another time maybe.

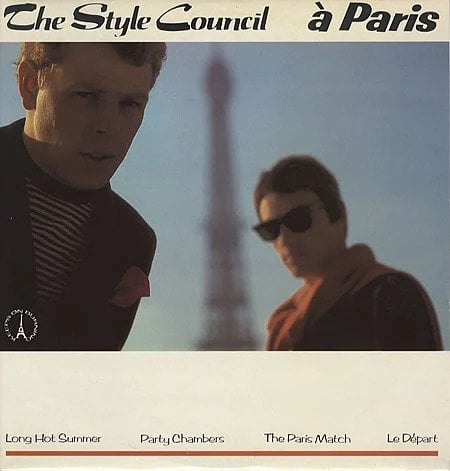

And now it’s somehow 40 years since The Style Council adventure truly started. The filming of the ‘Speak Like a Child’ video was really early on. It looked bloody cold that day on the top deck of that open-top double-decker.

“It was very cold! The film crew said they’d bought us all these thermals, but we thought, ‘We won’t need that.’ Then we went there and thought, ‘Bloody hell, we will!’”

Was that on the South Downs?

“Yeah, I can’t remember exactly where. They do spring water there.”

Not Peckham?

“No! Ha! It was a long time ago!”

It’s certainly an iconic video, one of many such quality promos you made.

Yeah, I think it just embraced that thing. Like you said, a lot of pressure lifted for Paul. On the other hand, a lot was expected of him, but he didn’t seem concerned with that. He just seemed concerned with doing what he wanted to do, pleasing himself and being a bit more in control of things. And the first 18 months saw us not being focused on specifically having to do an album, doing a lot of singles, a lot of different things, and not going on tour that first year…

“Someone said the other day, we put out about 18 or 19 tracks before we even got to our first album. That’s only four or five singles, but there were different versions of different songs, B-sides, unique tracks, 12-inch versions and all sorts of different things. We were allowed to experiment and develop ideas and not have one eye on, ‘Will this work live?’ or ‘Is this part of an album?’”

Last night, I found myself rewatching the Goldiggers nightclub performance from Chippenham for BBC’s Sight & Sound in Concert in March ‘84, which I hadn’t seen for a long time. One thing that came over to me was that with your Hammond touches and everything else about the band, you avoid the dating aspect of the production that so much pop from that era now suffers from in that era. And that was the first UK Council Meeting, wasn’t it?

“It was, and it was a bit mad, really! Quite a young band, our first gig, and it was televised!”

You look really together, all the same.

“I can’t remember the chronological order. We may have been to Europe, but it was certainly the first day of a UK tour. We’d had a bit of a break, and I just thought, ‘Anything could happen here.’ Usually, you’d get a bit of a run-in and be about six dates in when you’re doing the telly, so everyone should be together. But we just did it.”

I’d kind of forgotten that it was a pre-Brand New Heavies era Jaye Ella-Ruth, then known as Jaye Williamson, singing out front, rather than Dee C. Lee, and on fine form too.

“Yeah, I think Dee wanted to do it, but she’d just signed to CBS and was too busy. She was keen to come back, and did come back. She had to speak to her management and say, ‘I want to try and make both these things work.’ It wasn’t impossible, but in the early days, it was a bit of a problem.”

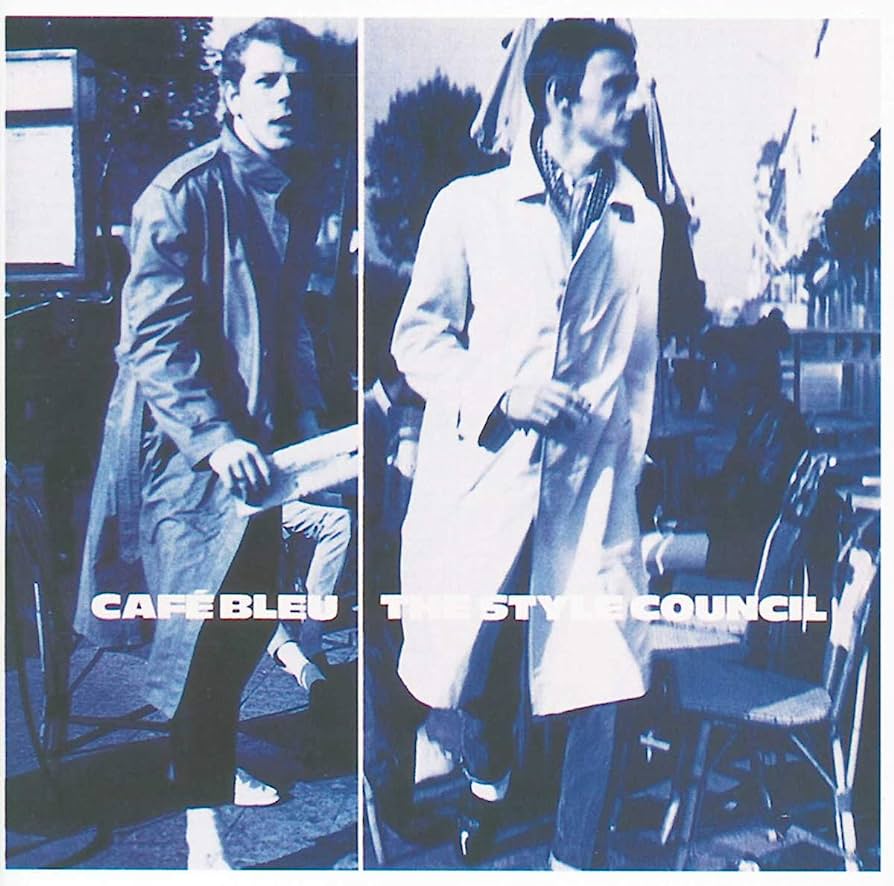

I’ve undergone my own Style Council revival of late, reminding myself of a golden period in the history of classic pop fused with so many more sub-genres, embraced by a happening collective at their creative peak, with Paul and Mick at the helm and kudos due to Steve White, Dee C. Lee and all those involved with them to some degree or other on that epic journey. Such a great run of singles for starters, and the first two albums in particular resonate with me to this day.

Take by way of example the sheer joie de vivre of 1984’s Cafe Bleu, a wonderfully diverse collection of songs aptly bookended by ‘Mick’s Blessing’ and ‘Council Meetin’, not just for the hits, but the amazing scope of influences within, personal ‘rediscovered’ favourites of late including ‘Here’s the One That Got Away’. And then came ’85’s Our Favourite Shop, a near-perfect example of politics meets pop that nailed that whole era yet sounds just as sharp and relevant today. I was sold on its worth long before turning over to side two.

So many of those songs played a key part in my youth and those of countless others, and I could talk about many more numbers, but as someone with strong Woking links – family and football – I’ll get onto ‘A Solid Bond in Your Heart’, the promo video filmed at Kingfield, one of those moments I take pride in, as I do when I see Paul walking the back alleys of the town my dad and grandparents grew up in ‘Uh Huh Oh Yeah’. They both take me back to a time and place.

“Yes, and Nicky Weller’s running an event there, and said to me it looks the same from outside but it’s totally different inside.”

Indeed. And will you be there in your porkpie hat, DJ-ing, on this occasion?

“Ha! No, I don’t think so. But I think I’ll be chatting to some DJs! They’re having a weekend of events, and I think there’s a couple of guys focusing on the Cafe Bleu album, so that’s going to be the framework, playing snatches from every track, asking me to reflect on them. And I’ve a feeling there’s going to be a panel as well. I think Camelle Hinds and Jaye are involved. And Stewart Prosser, who was part of our horn section. A four-part panel chaired by Dan Jennings, who does the Desperately Seeking Paul podcast. And he’s really good.”

That he is, with more details and ticket information about the Here Comes the Weekend two-day event at Woking Football Club (this Saturday June 24th and Sunday June 25th) at the end of this feature/interview. And was that storyline in the video for ‘A Solid Bond in Your Heart’ something of an amalgam of yours and Paul’s youth club days?

“Ha! I always think that’s the people we would have liked to have been or looked up to when we were about 12. There was no way I had a Ford Cortina when I was 12!”

Fair point, well made.

“But they’re probably fictionalised versions of older people that we looked up to in around 1970.”

When was the last time you watched The Style Council’s 1987 film, Jerusalem?

“Ha! I haven’t seen it for a long time, but sometimes people might show me a clip and ask, ‘What’s all this about?’”

You could probably ask them the same.

“I was at a birthday party at the 100 Club when somebody asked me what it was about. God, how many times do I get asked this question? My mate said, ‘Come on, don’t shy off, tell him what it’s about.’ And I just went, ‘It’s about 35 minutes.’ That was the best way of getting out of it. But on reflection there’s lots of salient points made about society that still stand up. It doesn’t really hang together that great, but in a ham-fisted way we were trying to make some points about things.”

It at least makes more sense than The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour.

“Ha ha!”

What was more fun, those early Council Meetings, Brockwell Park for the CND benefit, Live Aid, the Royal Albert Hall finale in early July ’89… or is there another date that jumps out above all others?

“Well, I suppose Live Aid was just such a one-off, and that does stay with you. That was a bit sort of unknown and something to remember. I do remember other gigs, but what helps me with these things is when somebody tells you about the gig that you are at, and you think, ‘Oh, I forgot that’. I bumped into someone from Glasgow and he reminded me we played the very last gig at the Apollo and it was going to be knocked down, everyone taking souvenirs at the end of the gig, ripping up the seats and taking a part of the theatre with them, because they knew they were just waiting to get the wrecking ball on it.

“We even got the crowd singing, ‘It’s coming down on Tuesday,’ chanting en masse, which is quite something with a full house of Glaswegians!”

That’s certainly sounds more advanced than those cries of ‘We are the Mods’ you hear on the Goldiggers footage.

“Yeah! I met a guy in Soho who was from Glasgow, and he remembered that fondly, saying, ‘I can’t believe you got the whole crowd singing that!”

Fantastic. And ‘Headstart for Happiness’, ‘My Ever Changing Moods’… there’s so much joy in those songs. I particularly love that whole era and Our Favourite Shop. You’ve mentioned before how much work you put into that sleeve cover, all those influences represented. And I was just another punter who loved looking at that detail, wondering, ‘What’s that in the corner?’ That’s what I call legacy.

“Yeah, it does draw people in. And I know there are people that have tried to source everything in that. People come up to you and go, ‘Was that Hancock book yours?’ I go, ‘Yeah, that was mine,’ and they say, ‘I’ve got that, but they’ve changed the cover. I can’t get it!”

Well, that takes it to a different level.

“I know. I mean, there’s some things that are in it that you can’t actually see in the picture. But I can kind of remember they were there. So I just think, ‘Well, even if you think you’ve got everything in it, there’s things on the counter that didn’t appear but I know were there!’”

Can you give us an example?

“Oh, I don’t know!”

Go on, the internet could go mad when this goes live, with E-Bay bids everywhere.

“Ha! I think I probably had a membership card to Wimbledon Tiffany’s or something like that, with Mecca written on it and ‘Michael Talbot No.479’ or something.”

Fantastic. And if you count from the day Steve Brookes left The Jam in the summer of 1975 with the adoption of those Jam suits and them trying to break that London scene, heading towards the Polydor deal, the punk scene and fame, through to the break-up in late 1982, it’s a similar timeframe to that of The Style Council, which stretched from the start of ‘83 to Summer 89. Is that about right for the shelf life of a young and happening band, do you think?

“Well, maybe it is. I don’t know if we kind of exhausted people’s patience. The thing is, the liberation and freedom that existed within The Style Council to just try things…”

… and right to the end.

“Yeah, we always had the same sort of mantra and idea about the way we approached things. It was a game of two halves, and the first three years were more readily accepted than the second, I guess. And in a way, we were just fortunate that people did like it.

“The great thing about a record is that it is that – a record of what you did, and it stands there. I can find something that was recorded 100 years ago that I’ve never heard of, but I will have to play every day for the next fortnight. And that music is just enduring and if it’s been captured on some form of recording, that’s the magic – yep, I’m back to that sort of magic of it all. It’s enchanting.”

And that can include the whole look of it, the record sleeve and so on.

“Yeah, even that. And even at our very worst there was something worth checking out. I’ve encountered people that have just got the album that didn’t get released originally, saying, ‘I understood it, I got it!’ But I’m like, ‘Did ya? I don’t even know if I did!’ But then people are so engaged in something that’s gone on in the past that it’s really quite nice that people can have a personal connection to something that is true, regardless of when it came out.”

People often talk about you personally, your sense of humour and down-to-earth nature. I’m thinking you’ve always had those qualities. I can’t imagine you ever getting above your station and becoming a rock star.

“Well, y’know, there could be stories out there! I sometimes think when you’re in a band and you’ve got a real successful thing going and you’re on a high, there’s a kind of collective arrogance. Which probably doesn’t necessarily reflect me personally. It’s almost like a professional thing of confidence in what you’re doing, regardless. And if people talk to me about that sort of golden age and say, ‘We met you at so-and-so,’ I’ll say, ‘I hope we were nice to you!’ Because sometimes the world’s spinning so fast, when you’re at a certain sort of trajectory of your career that you can be seen as being like that… but I’ve never striven to be aloof!”

When you first got sight of the Paul Weller Movement in late 1990 or heard that self-titled debut solo LP in 1992, was there a hint of regret for you that you weren’t involved in this exciting new chapter in your pal’s life and career?

“Erm, not really. There was a bit of an overlap for me. There was a song that we co-wrote that was on his first album, ‘Strange Museum’, which was still kicking around, and then I played on the second and third album. Not that many tracks. So there was a sort of connection there. But no, I enjoyed it, even though sometimes you hear things and think, ‘Oh, that’s right up my street, and I might have done something a bit different on that.’

“But what really engaged me about Paul’s early solo career was the fact that he had the confidence to play keyboards. He used to do little bits and pieces on some of our things, but quite often if he’d written a song at the piano, I was always wanting him to play the piano. I know that sounds a bit mad, like you’re talking yourself out of a job. But there’s something pure about the composer and singer playing the piano and singing, in a way where you don’t have to be Liberace or anything.

“To me, it’s like when I hear Neil Young play piano, or John Lennon play piano. Even though John Lennon had Nicky Hopkins on board, the piano on ‘Imagine’ – the song, not the album – is John, even though he had one of the best keyboard players sat there in the studio while he did it. It’s something pure that sort of connects to the voice. Which you try to do if you’re accompanying someone.

“When we did the piano version of ‘My Ever Changing Moods’, which is just me and Paul, I was trying to get into his head – you’re trying to sort of become one. But when it’s one person, it’s got something really good about it, like ‘You Do Something To Me’. I thought, ‘I’m so glad he’s done that. I imagine if he’d knocked that out about 10 years earlier, he’d say, ‘I’m not that great on piano, can you play something similar to what I’ve done here?’ And I’d say, ‘But you sound alright!’

“So I was pleased that he’d got to that point, because I think some of his strongest stuff involves him on the piano, leading it, like ‘Stanley Road’, the track.”

You’ve continued to play with Paul on his solo material, you’ve released albums with Steve White as Talbot/White, and alongside Steve and Damon in jazz/funk outfit The Players. You also returned to Dexys, all those years on, you’ve worked with Jools Holland’s band and Stone Foundation. And there’s so much more, from work with Dexys/Bureau pal Pete Williams to Galliano, touring with Candi Staton, guesting with The Young Disciples… You’ve clearly still got that hunger. And like Paul, you still seem to be discovering and falling in love with new and old records alike. Do you have long-term plans or is it just a case of answering that phone now and again, then on to the next project?

“It’s just whatever comes up really. I don’t know if I’m fiercely ambitious. I just like playing music, and sometimes it can be with two mates in a room above a pub with a borrowed keyboard. I had one week, 20-plus years ago, where I played the Blue Posts, a pub around the block from the 100 Club, upstairs at an open mic night – three tunes with my mates, one on ukulele, one on acoustic guitar, and me on electric piano. That same week, I played the Royal Albert Hall, one of four keyboard players at a Hal David and Burt Bacharach charity gala in the year 2000, with Dionne Warwick, Petula Clark, Sacha Distel, and all sorts of names. Then, about five days later, I played Glastonbury with Ocean Colour Scene. That’s not necessarily a typical week, but…

“And probably the best gig was the one in the room above the pub! And we weren’t paid for that. We just got a free drink.”

There must have been some ‘pinch me’ moments along the way, such as working with Wilko Johnson and Roger Daltrey in 2014 on the Going Back Home album, and also with Daltrey and Pete Townshend on a single that year.

“That was amazing to get asked to do that. And it’s sad to think Wilko’s gone now, but he was supposedly ill then, and that’s nearly 10 years ago, so he confronted that disease and overcame it for such a long while. We all thought he was invincible.

“He was a complete one-off, and very important to the whole scene. And when I first clapped eyes on The Jam, I just thought, ‘This is the junior Feelgoods really,’ in a visual way. I think Wilko had just left Dr Feelgood, my favourite live band at the time, but I thought, ‘This is the new lot. This is the next step on.’”

Here Comes the Weekend is a two-day event being held at Woking Football Club on Saturday June 24th and Sunday June 25th – celebrating the music and influence of local hero, Paul Weller, and his groups, The Jam and The Style Council, co-curated by Paul’s sister Nicky Weller and Stuart Deabill.

As well as Q&As with bandmates, designers and photographers who have worked with The Jam, The Style Council and Paul – also including esteemed photographer Lawrence Watson, art director Bill Smith, and The Jam/Loose Ends brass supremo Steve Nichol – there will be a track-by-track discussion on The Jam’s All Mod Cons as well as Café Bleu, with Stuart and Joe Dwyer from The Perpetual Motion Radio Show.

There’s also music from tribute act The Style Councillors and up and coming outfit The Molotovs, DJs Sonny and Suited and Booted, the afore-mentioned Dan Jennings, MC for the weekend and main interviewer. And there will also be stalls selling clothing, records, books and other merchandise, a scooter ride-out, plus a sold-out Tufty tour each day before the gates open, lifelong friend Steve ‘Tufty’ Carver, taking in local haunts and hangouts from his and Paul’s formative years. For more info and last-minute tickets, try this Facebook event information page and ticket link.

With extra thanks to perennial Boy About Town Mark ‘Bax’ Baxter for the introduction to Mick.