In which Malcolm Wyatt publishes further excerpts from Wild! Wild! Wild! A People’s History of Slade, in this case the full-length version of his late April 2023 feature/interview with esteemed South East Cornwall-based photographer Gered Mankowitz

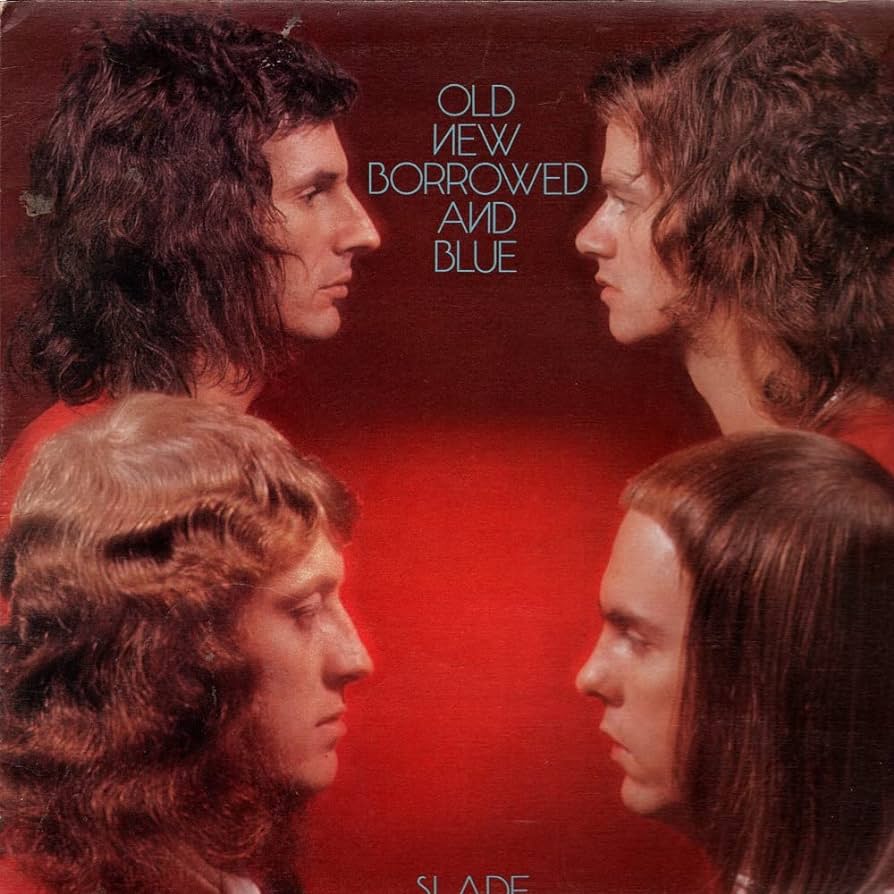

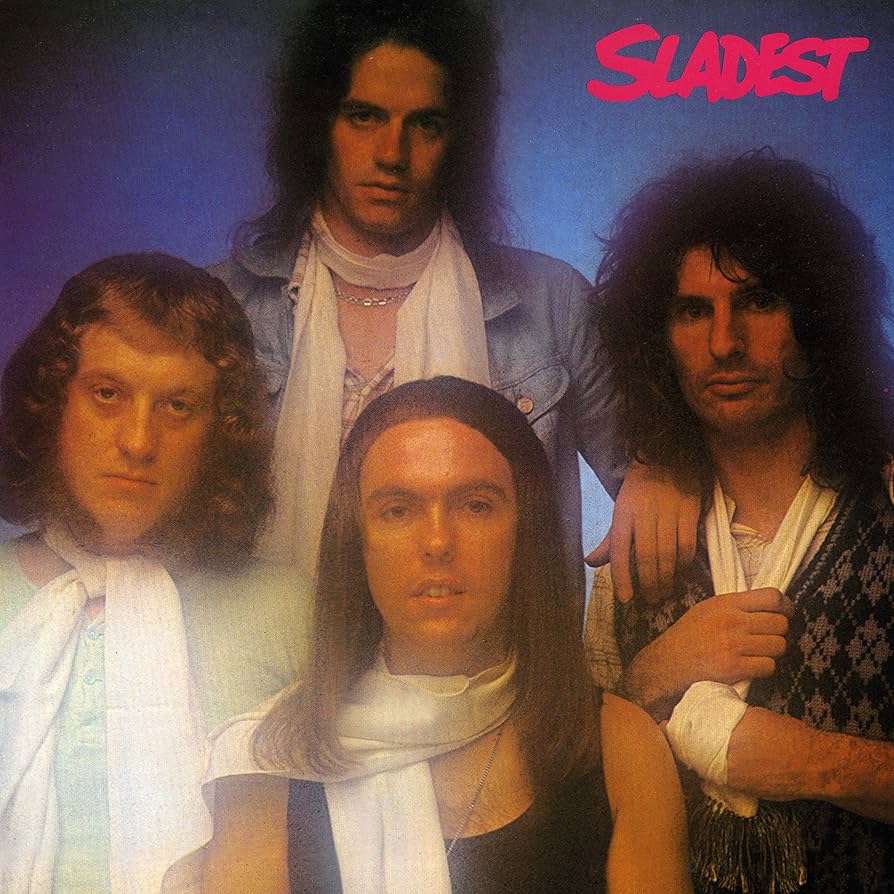

In Gered Mankowitz: Rock and Roll Photography (Goodman, 2016), the legendary photographer wrote, ‘I loved Slade! They were always fun to work with and I ended up shooting over 35 sessions with them throughout their long and distinguished career. I shot almost every album cover they did, and many other sessions as well. They were hugely talented and made an endless stream of brilliant, raucous pop hits, throughout the Seventies. I considered them to be good mates and am still in contact with Noddy Holder, and recently had tea with Dave Hill and Don Powell when they played a local gig.’

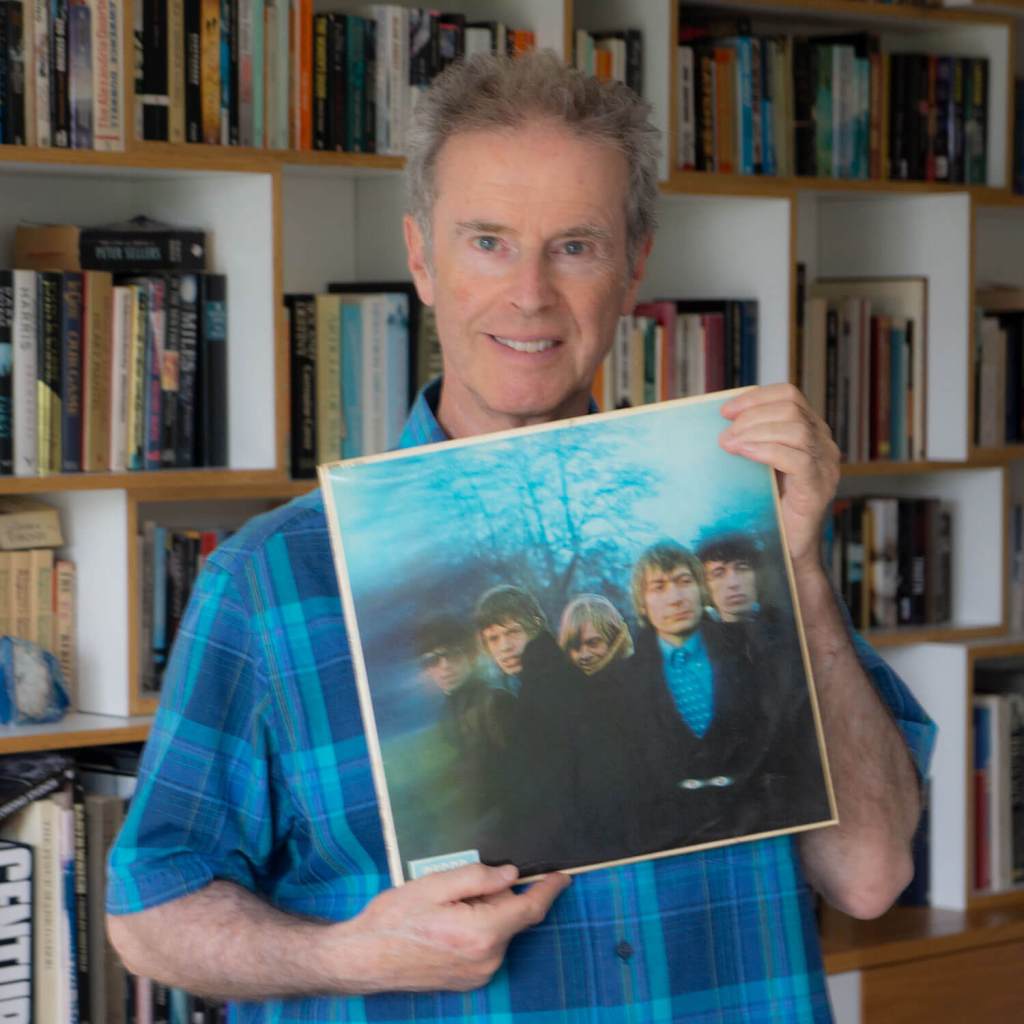

That was all I needed by way of an excuse to track down the man himself to his South Cornwall home studio on the lead up to publishing Wild! Wild! Wild! A People’s History of Slade (Spenwood Books, 2023), Gered, now 77, apparently inspired to take up photography by comedian Peter Sellers, opening his first studio in 1963, going on to work with Slade from the turn of the Seventies.

Finding himself at the centre of Swinging London in the early Sixties, Gered worked solidly for the next five decades, his many iconic images – from ABC and AC/DC to Wings and The Yardbirds – also including those of Duran Duran, George Harrison, The Jam, Jimi Hendrix, Kate Bush, Led Zeppelin, Madness, Marianne Faithfull, Oasis, the Rolling Stones, Small Faces, Status Quo, and Wham!

But how did Gered end up working so closely with Chas Chandler’s Slade, at such a key time in their development, building such a creative, successful working relationship?

“I started working for Chas in ‘67 when I photographed the Jimi Hendrix sessions. I did two with Jimi and the Experience. I was trying to remember how I got to know Chas, because I never photographed The Animals, so there was no obvious link. I think it was because I was doing work for Rik and John Gunnell. They managed bands and I’m sure Chas was involved in some way. He asked me to photograph Hendrix, and we remained in touch.

“I photographed other artists for him, and then he approached me to photograph Ambrose Slade, in, I guess, ‘69. I don’t know the exact chronology, but as far as I know it was their first session since moving to town.”

I get the impression that past experiences with photographers and record label types, through their earlier label, Fontana, helped them wise up, as suggested by ‘Pouk Hill’ on 1970’s Play It Loud, written about their experience of a Black Country photo-shoot with Richard Stirling for sole Ambrose Slade LP, Beginnings, the previous year.

“I don’t know that story, but they were quite independent in their thinking, even then. And Dave {Hill} was very opinionated, very full of himself. But I enjoyed their company from the outset, and I think they enjoyed mine. And it was the beginning of a long-lasting, very productive, lovely relationship. I mean, I loved them dearly, and consider them really good friends.”

I guess 30-plus sessions together tells its own story.

“I think there were over 40. They were fun to be with, extremely creative, and it was always a very positive experience being with them. They were never moody or difficult, and they had a real sense of their identity. It was always a very enjoyable working relationship. We had fun. We were always giggling, and they were great piss-takers.

“Gosh, they used to tease me, based on a character in a famous Tony Hancock episode {The Publicity Photograph}, very funny, where Kenneth Williams played the photographer. For the life of me, I’ve forgotten what he was called, but they’d call me that. ‘He paints with light!’ Yes, it was a very friendly, very enjoyable, productive time.”

Hilary St Clair was that character, by the way. And of all the Slade record sleeves Gered shot, does one stick out above all others? Several certainly became iconic images.

“I was going to say Nobody’s Fools. Not because of the sleeve, but because of the session. I didn’t like the sleeve. Between them, Polydor and Chas messed that up. I wanted the black and white version with coloured red noses, which I thought was a vastly superior photograph. I think it would have worked really well. But record companies wanted colour for some reason, and they did a horrible thing to the picture.

“I liked the session very much, and thought the band were looking extremely polished at that point in their identities, their images visually really refined. I’ve always loved the black and white pictures from that session. That stands up, and Play It Loud, because that was quite a breakthrough picture at the time. It wasn’t a sort of natural cover image. I was very proud of that and enjoyed most of my sessions with them.”

One that strikes me from those earliest sessions is where you’ve got them sat with boots forward, in skinhead garb. And in at least a couple of cases, they look anything but hard.

“I know! Again, the exact chronology escapes me, but Chas rang and said, quite soon after I’d done either the first or second Ambrose Slade session, ‘You better get back here… quick,’ so I did, and we did the skinhead session. The thing is, they were so sweet looking… Don was possibly the hardest looking, but they just look sweet. And Dave, I mean, he looked like a baby!”

Not really the image Chas envisaged, I’m sure.

“They certainly didn’t look hard, but I guess with the music and the boots and stomping around on stage, it tapped into that skinhead vibe.”

It seems that some of that skinhead crowd of the time stuck with them too, long after the hair grew back.

“With the beat, the raucousness, and the quality of the band, they were something to watch. And they were a major band, awfully good. Maybe it’s something to do with the Seventies as a decade, but Slade were an incredibly important powerful band and a huge influence, yet they’ve never been a band whose merit has not been truly assessed.”

I’ve found time and again – perhaps chiefly because the musicians in my contacts book are mostly drawn from the punk and new wave era rather than the heavy metal followers that latched on to them after the 1980 Reading Festival – there was a year zero approach to what came before 1976 and all that. A lot of emerging acts kept it quiet that Slade were an influence, from early sightings on Top of the Pops onwards.

“I think that’s true, and very interesting. I’m not a music historian, so I don’t really think about it in terms of when things happened. I just know they happened, and Slade were a great band… and important.

“I’m always singing the praises of Slade, whenever I get the opportunity. Whenever anybody asks who my favourite bands were, I always include them, and enjoy talking about them. And everybody at the studio loved them. When we had the studio in Great Windmill Street {Soho, London W1}, pretty much throughout the Seventies, they’d come several times a year.

“We’d have a big Christmas party there. I’d cook a turkey and a ton of sausages, and we’d make a huge punch, famous for being an absolute killer punch. You had absolutely great sounds, and we invited people from all walks of life, and we’d invite Slade and their roadies, particularly Swinn {Graham Swinnerton}. They arrived, one year, were almost the first there, and I’m at the door welcoming people, saying, ‘Great to see you, go right through, there’s food over there.’

“After about 20 minutes, I managed to escape the door, went inside, and the turkey had gone, the sausages had gone, and Slade and the roadies were just sitting around. ‘Great grub!’ They cleaned us out in 20 minutes!”

I’m proud to say the forewords for Wild! Wild! Wild! A People’s History of Slade are from two of your other past subjects, Suzi Quatro and Sweet’s Andy Scott.

“Yes, two other friends, and I’m still in touch with both. I adore Suzi, working with her throughout the Seventies, up until relatively recently. She’s somebody I like enormously. And I did the pictures for the band Suzi, Andy and Don Powell formed {QSP}.”

Having spoken to Suzi, I had to have a quiet word with my 10-year-old self, the young lad who’d be in awe of her stage appeal for five years by then, from Top of the Pops appearances but also those record covers and so many of your iconic shots.

“That’s nice to know. The thing is, certainly back in the Sixties and Seventies, seeing bands wasn’t as easy as perhaps it is today with social media and everything, so those pictures were very important. And that first vision of the artist is very important.

“In the early Sixties, you’d listen to bands on Radio Luxembourg and have absolutely no idea what they looked like and didn’t even know what colour they were or how many of them were in the band. You just listened to the music and thought it was great. But image became increasingly important, and those primary images become iconic images if you’re lucky.”

They’d had an amazing run, so arguably it had to end at some point, Slade out of popular favour on their return from the States, maybe part of the reason Nobody’s Fools is only getting kudos now.

“Well, the band didn’t stop being good. I can understand anybody saying it was a mistake trying to crack America, but they really had to do it. Chas was very much of the management school where if you didn’t make it in America, you hadn’t really made it. And the interesting thing is that they were incredibly important influences on several American bands.”

That’s something that happens time and again. The Rolling Stones, another of the bands you famously shot, recognised, to some extent replicated, and reinvented the sounds of the bluesmen of America, then took that music to new generations stateside, and some of those ended up in bands that influenced others on this side of the Atlantic. And so on down the years.

“Absolutely, talk about coals to Newcastle. But it needed an incredibly enthusiastic young band. I think it was much more of a tribute. They loved that music, Brian Jones in particular a real aficionado of that music. He really understood and loved it. I don’t think he wanted to do anything else. I think the blues was the bedrock of their success, and maybe the Stones had to have ‘(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction’, a global hit, to consolidate their career and success. And perhaps Chas tried to emulate that with Slade.

“The other problem is that you can get out of step very quickly, especially if you’re an important part of a previous step – and they were, for the best part of a decade. It’s very difficult when the mantle has been passed, to get back in. So that was a misstep, I guess.”

“But Slade were the complete package. Not only did they write the material, they looked the business and outperformed anybody else on the bill. They weren’t trendy. They were just there, and they were in your face. They were sort of unique.”

Those Black Country working-class roots and attitudes helped too. They were never pretentious.

“Yes, and I’ve just recalled another great night with them. I can’t remember the name of the pub, but I went to Wolverhampton with them to shoot some live stuff…”

Was it The Trumpet in Bilston?

“Yes, oh my God! We had such a great night. What struck me was that they were regulars and were truly treated as such, not as anything special. They loved that and were 100 per cent at home. Everybody loved them, nobody hassled them, it was a wonderful night. I’m not a big pub person, but I really loved that because the vibe was simply glorious, like being with a huge family.

“I haven’t seen Jimmy for years and years, but I’ve seen Nod, who sends me a shouty Christmas message and came to a couple of my openings at a gallery in Manchester. And I saw Dave and Don together when they were doing the rounds with {their version of} Slade at the Hall for Cornwall in Truro, having tea with them, which was great fun. And it was another incredible show, even though it’s not the band it was. I also had a nice time hanging out with Don when we did the QSP session. My feelings towards them haven’t changed. Nor has my sense of affection and admiration for them.”

You also did the publicity shots for Slade in Flame. What did you make of that film first time around, not least bearing in mind your own film background.

“I thought it was a very good film, one that tried to capture the music scene in an honest way. I don’t think I’d seen it by the time we did the pictures, but I enjoyed that session. It was very challenging, technically. We used a system called front projection. The suits we had made were very uncomfortable, difficult for the band to wear. We had to get the flattest surface to take the projection cleanly – if it increased, it gave you horrible grey lines. It was complicated.

“They had to be very disciplined, and I had to be very disciplined. But it was very successful, the pictures memorable… and they worked. I’d quite like to see the film again, if I could find it.”

Every time I see it, with the passage of time, I think it gets better and better. It really stands up, not least the opening scenes.

“Funnily enough, I was so close to Chas and the boys at that time, I had an idea for a television series, based a bit on The Monkees. I wrote up a brief script and discussed it with Chas, but he thought it was a bit too juvenile for Slade.”

Dave Hill has suggested to me before that he would have loved to have gone down that road. I get the impression he wanted a take on A Hard Day’s Night.

“I think everybody would have liked that. The idea of a television series built around a band seemed a really good idea. I know The Monkees had done it, but there seemed to be room to do it again, differently.”

Well, I guess Reeves and Mortimer went on to give us Slade in Residence. And do you still play the records, and if so, what songs jump out at you all these years on?

“Honestly, I’m afraid I couldn’t tell you. I like some of the slower ones. I always thought they were fantastic songwriters, the Lennon/McCartney of the day.”

A love of The Beatles often shone through, and I realise I’m talking to someone who enjoyed a good working relationship with George Harrison.

“They had to be. You had to be cut off from the world not to be influenced by and admire The Beatles. You might not have necessarily liked them in terms of image, but we were all in awe of and full of admiration.”

All LP cover images above shot by Gered Mankowitz and copyright of Gered Mankowitz / Iconic Images Ltd. 2023. For more about Gered, head to his website via this link. You can also follow Gered via social media on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

And to order a copy of Wild! Wild! Wild! A People’s History of Slade by Malcolm Wyatt (Spenwood Books, 2023), follow this publisher’s link, taking advantage of a 25% discount offer across all titles when using the code 2KQUCX7Q at the checkout. The publisher also has various other music publications up for grabs, including Rolling Stones, Cream, Faces, The Who, Pink Floyd, Queen, Thin Lizzy, Fairport Convention, and Wedding Present titles.

You can also order the book via Amazon, ordering through your local bookseller, or trying before you buy via your nearest library.